Black and White, but never Gray

Robert Gray had what they call in politics a mongrel streak, a readiness to bite—and be bitten.

BLACK AND WHITE, BUT NEVER GRAY

The thing about Robin Gray, the once-premier of Tasmania, is that he’s polarising. You like him or you don’t, and there’s not much space between. And he doesn’t care, either way.

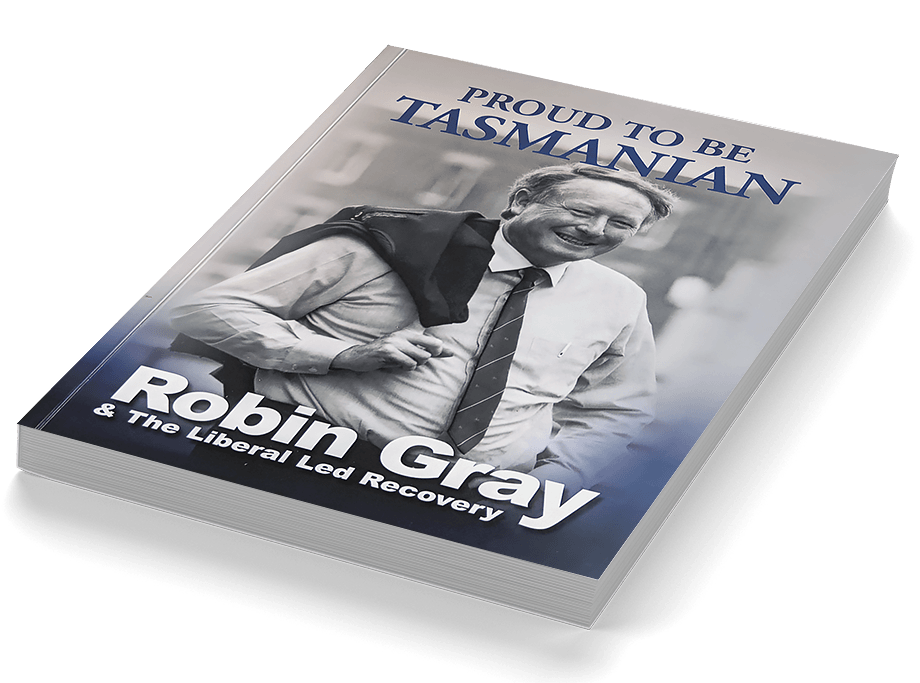

His just-published book, written with former head of office, Andrew Tilt, cedes not a millimetre of that turf, nor the forests, rivers or any of the other terrain on which he chose to do battle.

Called ‘Proud to be Tasmanian – Robin Gray and the Liberal-Led Recovery’ – a campaign slogan if you ever heard one – it lays out Gray’s view of the wrongs of the world that was Tasmania in the early 1980s. And what he did to right them.

Aside from The Dam and The Mill – more on that later – Gray largely succeeded. This book is his determination that his legacy not be forgotten; its physical forms of ships and infrastructure, buildings and businesses underpin much of today’s Tasmania.

The book claims to ‘fill the gap in historical publications’, yet leaves unanswered large gaps in a reader’s understanding of Gray, the man and his motivations.

In fact, he was an enigma even to those who worked closely with him, a private man through a very public career.

Certainly, Gray knew what he wanted and worked himself hard, and those around him, to get it done. Where no governmental entity or program existed to complete the job, Gray found the necessary instruments. And sometimes they were blunt instruments.

That speaks to the character of the man. Over six feet, large of frame and deep of voice, he eschewed small talk and the hail-fellow-well-met niceties of elected officials. Gray was not a natural politician.

His pre-political life as an agricultural consultant meant travelling Tasmania, getting his hands in the dirt, speaking the language of country folks, usually direct and colourful. Canvassing for votes in Wilmot before the 1976 election, it was much the same – travel and face-to-face conversation.

His huge appetite for work, alone or with a small group of peers, made him a formidable opponent on the hustings and Parliament. Wilmot, largely rural and Tasmania’s largest electorate, understood Gray; he outpolled all three sitting Liberal members at his first try.

He had behind him a northern private sector long suspicious of a government concentrated in the south. More, he had what they call in politics a mongrel streak, a readiness to bite – and be bitten.

By late 1981, Gray’s right moment-right time arrived. Barely 40, he became Liberal leader just as his Labor opposition fell, listless and lazy after being in power (with one brief interlude) for four decades, weakened by internal knife-fights, lacking rudder, vision or will.

Labor’s death spiral revolved around whether or not to build a dam on the Gordon River below the Franklin. The dithering and delays became a confusion of alternatives in which upper and lower houses of Parliament actually promoted their own separate preference.

To those of us in the media, it was like watching a suicide in slow motion.

The final act, on November 11, 1981 (yes, Remembrance Day) was to replace a besieged Labor leader, the Premier Doug Lowe, with Harry Holgate, who’d long manoeuvred for the top job.

The rupture, clearly visible through its elected members, reflected Labor’s vulnerabilities to union power and internal enemies. Lowe was caught between a pro-dam union base and the party’s natural allies, a nascent but vocal constituency with an environmental bent.

Holgate’s was a desperate act and he knew it. At his 1981 Xmas party for the media, the new premier was clearly nervous about the upcoming election.

When I gave him, a little mischievously, a tube of superglue as a gift, he asked what it was for. I suggested he spread its contents on his chair, and then sit on it. “It may help you keep your seat,” I offered.

Holgate lost the Premiership to Gray on May 15, 1982. He’d held the position for barely six months.

(Curiously, Gray’s own replacement of Geoff Pearsall as Leader of the Liberal Party, just hours before Labor’s switch to Holgate that very same November, had been lost in the news shuffle.)

Now Gray was ready to rout enemies and right wrongs. It was time, to use an expression much used around the office by Gray and Tilt both, “to crash through – or crash.”

At his back were two superior politicians, Max Bingham and Geoff Pearsall; both of whom had recently led the party, both versed in Parliamentary manner and form. They were political bookends for a man who’d only been in the House for six years and Liberal leader for only as many months.

Bingham’s part, in particular, requires acknowledgement. An Oxford law graduate, Rhodes scholar, he was a QC and later headed the Criminal Justice Commission in Queensland. Attorney General in the Tasmanian Parliament, he brought dignity, warmth and a rare intelligence, even trading pithy Latin expressions with his staff.

Geoff Pearsall, meanwhile, had the smarts to organize the government business in the house, to keep the opposition wrong-footed. It was Pearsall’s reward for his time in opposition and he took almost a wicked pleasure in using his new clout.

In government, Gray was often accused of being autocratic. Perhaps, but only if measured against his predecessors: he was going to make decisions and stick with them. And he was unequivocally a supporter of Gordon below Franklin.

More, he determined to control the information flow; those in the loop were kept to a minimum.

In the media section I became one of three – plus a first-rate secretary – a quarter of Labor’s media people. Everything government did and said was channelled through us… hard work, when some days 20 news releases went out.

Briefings came from Ministers and senior staff; we were rarely privy to Cabinet documents and their carefully articulated arguments for and against proposals. Elsewhere we dealt with queries from the media, sometimes enlightening but mostly politics as usual.

Then, the premier’s entire staff was just a dozen people including two imported researchers. The small number worked to form a cohesive unit: on more than one occasion, we were all in a single room in Parliament, an office, even a restaurant. Gray was most comfortable keeping things close.

He knew every one of us, heard us, trusted us. After I persuaded him to mount a penny farthing at Evandale (the newspaper photo captions – Going, Going, Gone – told the eventual story well) he recovered and in the quiet of the car, raised one oil-stained trouser leg. “I know who’s paying the drycleaning for this,” he said.

Running this outfit was Andrew Tilt, a hard-hitting political journalist turned Gray’s head of office, gatekeeper, strategist, enforcer. Like Gray, Tilt used his vocal gruffness to advantage, another blunt instrument. As co-author of this book, he’s clearly softened little.

In part, the book is a regular late-life political reflection, a view of the how and why of major decisions, a recitation of annual state of the state speeches, a list of accomplishments. But like politicians all over, it is in Gray’s failures that the real insights should be sought.

Question: How does a small group of people (his estimate is 10% of the electorate) hijack the Gordon below Franklin dam debate, confound media and public alike, involve the Federal government, and get the decision of the Tasmanian people overturned?

For this movement, the Tasmanian Wilderness Society (TWS), new truths were created. It became the Franklin dam, (we’re stuck with it, even in Wikipedia) despite being on the Gordon. The Franklin was now “Australia’s last wild river,” a dubious claim at best. Stunts like sending rafters downriver were invented to grab media attention.

And in a moment of inspiration (that ought to be the lead paragraph of every pr handbook), the TWS set up headquarters at Strahan, as physically close to the proposed dam that telephone lines would stretch.

From there, the media – Australia and the world – got an uninterrupted briefing of what was going on. Just not from the people actually building the dam.

Gray’s failure was 300 kilometres away, back in Hobart. Yes, multiple other issues and Parliament required his close attention. Yes, he’d comprehensively defeated Labor on this very same dam question. Yes, he had support across the entire apparatus of government.

But in this re-energised dam debate, the opposition was not a familiar political enemy, but an outside movement propelled by emotion and a leader of almost messianic proportions. The battleground was wherever Bob Brown said it was. And it kept moving.

The usual dictates – political will, union and industry support, the backing of the ballot, an agreed set of facts – just did not apply.

The push-back against the TWS campaign fell largely to the Hydro Electric Commission – engineers, scientists and construction experts (and one media guy) – but not a one of them was ready for pitched battle against the TWS, its guerrilla tactics or media savvy.

The Hydro was a blunt instrument of a different type. Heavy and slow-moving, it had never had to sell its product, justify its actions, rationalise costs. It had no strategy, experience or expertise in dealing with opposition of any kind. The dam was dead in the water.

Ultimately, Gray could have done little to stymie what Labor had done with its final, desperate pitch to the Commonwealth for World Heritage status for the area that included the proposed dam.

In those first days, we understood little of this deliberate act of sabotage, committed as Labor left government.

But revisiting that period raises more questions. Should Gray have formed a specialist team to take on the TWS and Bob Brown, pushed back on every half-truth, driven back every challenge? Did he under-estimate the TWS, not once but a second time on the Wesley Vale mill?

Today, Gray still privately rages against journalists he considers had it in for him over his time in office, people he considers left-wingers. And his book makes it clear he has no love for Bob Hawke, or Bob Brown. The battle is not yet done.

On the other hand, Gray will smile – his sense of humour is under-appreciated and largely unseen in the book – knowing that when Dr. Brown needs to leave his home town of Cygnet, he does so on a highway, the Huon, that Gray built with dam compensation money.

Perhaps the current government should rename it.

THE WORLD ACCORDING TO KERR

THE MAN HIMSELF

THE NOT SO REAL WORLD

THE KERR-LECTION