According to Kerr

Stories, insights, and musings gathered along the way.

-

She came to the point faster than I expected.

“And what did you do on the tour?”

It was tempting, in that moment, to lay out the entire story, to extend my seconds in the sun for as long as possible and ensure my absolutely critical part in the entire venture was recognised at the highest level.

Instead, I kept it short and – what ultimately proved to be – sweet.

We had in fact spent some months preparing for this moment, along with the whole three days of moments that preceded it. No, it wasn’t me, but ‘we.’ And the ‘me’ part was actually pretty damn small.

Alice Springs had greeted us with an official reception about ten days earlier, a get-together of all the officials assigned to the six weeks in Australia; some were protocol and others transport, some security, and others like me, communications. Media liaison if you like.

It was my first trip to the Alice and the Red Centre. It was a disappointment, and not even red: a once-in-ten-years rain had rendered Alice green from horizon to horizon. As for the reception, I didn’t get close to the centre of the action. Nor was there any sign of a babe in arms called William.

Anyway, I had work to do back in tiny Tasmania.

The job had come to me in a pick-a-straw kind of way. One of three comms staffers working to the state Premier of the time, assignments occasionally arrived in a conversation that began with some version of ‘you don’t look too busy’ and ended up with me at my IBM Selectric late at night.

Other than to extend my media wrangling skills to dealing with a sizeable crush of British and local media there wasn’t anything much in the way of an accompanying job description. I decided to go active and set about creating one.

With a thoroughly vetted itinerary from the Chief of Protocol (a nice man called Leo) I dug out a slew of information about the geographic elements of the tour – even a solid bit of automotive research on the Daimler that would serve as their primary vehicle.

I wrote up a hefty 80 page compendium of the three days, carefully typed and re-typed on the IBM, then the epitome of office machinery. The work would serve as a solid reference base for the media horde about to descend on an island that is always green, horizon to horizon.

And by focusing on the facts, a dry recitation of where they’d stay, go, see and stop, I managed to keep some distance, some semblance of sanity, between me and the brouhaha that lay just ahead. It was, I told myself, just a job.

On the top I typed: Tour of their Royal Highnesses, Prince Charles and Princess Diana, March 30-April 1, 1983.

It began with an airport arrival, a motorcade and then a trip into town on the Governor’s motoryacht, the ‘Egeria.’

For the length of the tour, south to north and back again, out came the crowds and kids with flowers and flags, waves and cheers—everybody caught up in a crush to see a newly minted English princess. Beautifully planned and organised, everything ticked over like clockwork.

Almost. There was one moment, a day later.

At the Maritime College in Launceston, the side wall of a massive indoor pool has been mocked up to look like a ship. We’re there, on a platform some 15 metres above the water to see an exercise, an evacuation of the vessel into the water below.

There’s shouting, whistles and klaxons and flashing lights and lifeboats being lowered and god knows what else. Then the overhead lights go out.

In the sputtering semi-dark, my attention is drawn away from the action and noise to the area immediately in front of me, where there’s a slight whoosh of air and a thump. An English voice eventually pipes up and asks, somewhat apologetically: “Would someone mind awfully turning the lights back on?”

The explanation for the lights going off, we discover later, is what we were there to see was actually a night-time exercise. It was a rare mistake in a meticulously planned schedule.

There isn’t an explanation however, for what was in front of me as the overheads came on again. The future king of England was covered by a rugby scrum of security, police officers in plain clothes. That would explain the whoosh of air.

But at the edge of the viewing platform is Diana, Princess of Wales. She is in all white and entirely alone.

Such, I assumed, were the instructions to the security detail. For my part, I was happy enough we’d not had space for the media on that platform on that day. The scene, brief and befuddled, was, at best, awkward.

The matter wasn’t mentioned again.

There are photos taken over the three days where I’m clearly in combat mode, the veins in my neck and arms standing out, close to shoving someone’s camera up their British backside. But mostly I answer the media’s questions as best I can, referring to the 80 pages of notes I’d provided each of them.

I’d earned some cooperation early in the schedule, at the official reception in a ballroom of Wrest Point Hotel. It was then the only space large enough to pack in the few hundred dignitaries deemed worthy of the occasion that was the first visit to Tasmania of the Prince and Princess of Wales.

The media contingent was arranged in a chevron ahead of the stage, a triple-row affair with the first line on the floor, the centre sitting and the rear standing. That way, every photographer, cameraman and journalist in the media pool got a clear view as the official group moved through the room.

Charles and Diana, the Premier and party were closing on the platform as a short gentleman in the front row of the pool suddenly stood up. Behind him, the ranks of his colleagues started to shift to compensate, the careful formation breaking apart.

I leaned forward and spoke with one of the security guys, explaining that I thought the gentleman in the front row was in need of some air. There was a blur of movement as Mr. Short was escorted out and the triple-row chevron snapped back into shape. I breathed again.

A little later, Charles’s media guy (HRH also has one dedicated security man, a British bobby) turns out to be seriously laid back. He’s worked for Pierre Trudeau, seen more of the world than me. Over a pack of Marlboroughs and multiple drinks, he encourages me to chill out. I learn enough that I don’t need to ask why Diana doesn’t have her own media or security person.

Nonetheless, I can’t quite get my head around the media. Not then, not now.

The media on the tour -- the British more so than the Australians – is a fermenting madness. Some kind of feedback loop has developed between the clamour of the crowd and the media’s closely honed sense of what sells papers, magazines and TV news. More, more.

They are intrusive, constant and unrelenting. Motorized camera shutters fire off like the rattle of a high-speed tram -- close, deafening, metallic, frightening. It’s clear the woman on which they are trained is uncomfortable, unready for this, unable to relax for a moment.

Her every breathing moment is captured, every eye movement, squint and smile. Even the non-events get scrutiny. “They came ashore… the Princess somewhat gingerly,” says a TV announcer. “She doesn’t have too much seagoing training.” He divined that from one step on the dock.

Every glance and gesture, toss of the hair, flick of an eyelash, furrowing of a brow, is grist for the mill, chewed over and then filed for exhaustive analysis later. Her every word and footstep is being recorded and tracked. The photographs will emerge for years to come, their memory dismissed, their context distorted.

Had she a media advisor, someone able to push back, to demand space, privacy… But she doesn’t. She has Charles, who does have that kind of experience, that kind of backup, that kind of heft. But they are here to see her, and he knows it. She knows it too.

Who in their right mind would want to live like this? I ask myself.

It’s now the last hours of the last day. We, the contingent of local officials who’ve made the tour run like clockwork (or stop, in the case of the local trains) form a reception line at Government House, the vice-regal mansion on the city’s edge.

We’re there to be thanked for our efforts, presented with a signed and framed picture of the two of them. Shortly after, I’d be plunged back into political life, dealing with a stream of prosaic media questions about government actions and inaction.

It’s a tall-ceilinged but small room. Charles and Diana are flanked by a single uniformed equerry. There are no cameras; all is quiet. My turn comes and we shake hands as I’m introduced. Charles spoke, but it was Diana’s words I recall.

“And what did you do on the tour?” she asked.

“I was responsible for communications, the media stuff, ma’am,” I said, remembering the correct form of address and to pronounce it ‘ma’am’ like ‘jam.’ “Mostly, trying to get the press to keep some distance.”

“Ahh…” said Diana, laughing. “We usually use tank traps and barbed wire.”

“I’ll be sure to incorporate those next time you come,” I assured her. She smiled. It was warm, genuine, even a moment of understanding.

The interview, the tour, the moment, was over. -

The key to your car, of course, is far more than its predecessor.

Back in the day, a key was a crude mechanical device for completing a circuit, a chunk of cheap metal that slid into a slot, rotated clockwise about a quarter turn and got its wires crossed.

That was it.

The key now comes with a fob that’s the electronic boss, complete with its own chips and codes, even its own energy source.

Indeed, Captain Fob is the centre of an entire automotive universe, in command of something called the RF Transponder, and with that, everything from the car engine to lights and locks.

This brave new world is a radically different place from that which faced a young Kerr starting out on Life’s Voyage sometime in a previous century.

Back then, a missing car key was a minor inconvenience, a delay of perhaps minutes. We had long learned how to get a vehicle in motion entirely without a key.

It was a practical demonstration of necessity being the mother of invention.

For instance, my mother’s car was a necessity. If her key wasn’t available to me or my brother at the time of our intended journey – hard to believe, I know – we invented with wire and pliers.

The pair of us took to hotwiring cars like a politician to perks. In fact, mum’s car was needed for the borrowing so often that we installed a private, permanent hotwire – with a switch built in ! – between battery and starter motor.

The wire worked fine until one afternoon fire ignited the engine bay, and car became carbeque. True story. It was my brother’s fault.

But back to the current dilemma. I am key-less. And in this new world, Captain Fob at the helm, I am mere mug mechanic. I can gain access to the engine compartment, maybe even find the starter motor.

But can I still affix a wire to its nethers? What’s the likelihood my simple action will carbonize some sensitive (that is to say, expensive) component of that computer-controlled apparatus at the front of the vehicle?

Let’s remember how much it cost to repair my last automotive ‘repair.’

And let’s remember that a replacement key and electronic fob will be $300-plus, which was more than the entire price of my first car. And that key came free.

Right now, I really do need the current keys for the car. Wife’s bag? Never, ever a good idea. Could be bears, witches, giants in there.

Then there’s the No-Man’s-Land that is her side of the bed, not to mention the Don’t-Go-There recesses of the couch, among the half-finished, part-eaten and once-loved.

It’s even possible the car keys have made it to the very edge of the Kerr domestic universe, the eighth Circle of Hell that is our laundry.

What I need – what we all need – is a device, a TV-remote type gizmo that finds car keys by sending a signal to the key’s electronic bits.

There’ll be a beep, a blip, a burp… something to tells me where the keys are. Surely, such a thing could be included in the next generation of mobile phones? Find the key-finder app on the screen, press the virtual button, and presto!

Of course, before I can find my keys, first I’ll have to find my phone.

-

It happens very soon after you’ve arrived at that phase of the relationship where the two of you are living at the one address.

You’ve established some kind of routine to drop off the kids at school on the way to work. You’ve got the household chores divvied up and cobbled together a joint account to pay the rent and groceries.

Possibly the wine, too.

So now things are relatively settled, calm. Dare I say it, things are even humdrum.

It’s then she says something which shocks the man of the household – that’s you – right to the core.

And these are the words. “Honey? Can you make dinner for the kids?”

I know. Shocking, right? No way you could have prepared for this, or the suddenness with which it was dropped on you.

As you take a deep breath, here’s a little context and an understanding of how the female of the species goes about this very same task.

Read through, and you’ll see the glimmerings of a new world, a shiny place where you are a cook. The kids might even get a meal out of it.

Here’s the thing. When women go to the refrigerator, they find neat little packages: a dozen sausages, 10 hamburger patties, six lamb chops. And they pop them into the microwave.

When we men go to the very same refrigerator, there are two items in there that may or may not be food.

One is quite possibly the remains of the dinner you tried to cook last week. It now appears to be wearing a fur coat and green eyeshadow.

The other item is a 100 kilogram block of frozen Woolworths chicken, too large to be separated from the wooden pallet on which it was shipped.

How are you, man of the house, to turn this Everest of deep-chilled chicken flesh into an actual dinner? Bear in mind, you’ve got seven minutes before ‘Home and Away’ comes on.

I’m glad you asked. This is a test of your manhood, gentlemen, just a test, and this is how you do it. First, drag that chunk of chicken out to the kerb. Use a piano dolly, a wheelbarrow, a forklift if you have one handy.

And you’ll get a good grip of that slippery chicken skin by using those new tea-towels her mum gave you as a moving-in-together gift. You wouldn’t want freezer burn on those hands, would you?

Holding the chicken over the edge of concrete kerb, whack it – this is a technical term, gentlemen – whack it with your best hammer.

You probably have a quality masonry mallet close at hand, but I prefer a 28-ounce framing hammer. My Estwing has a good weight, great balance, and a very pretty blue handle.

So… two or three whacks, and as the greats of MasterChef would say: Voila! We have ourselves a chunk of chicken we can chuck into the microwave.

Oh? Still can’t quite fit it into the microwave?

Forget about the electric knife, even if you knew where it was. It’s time to drag out the big, bad boy, that chainsaw you’ve been saving for a very special occasion.

Strap on the Alaska edition, carbide-tip, all-purpose blade, and away you go.

I know, I know, you’re saying: “But Mike? A chainsaw? Won’t that leave a raggedy edge on the chicken?

And I say to you: “Yes, yes. But you just watch that special marinade soak right in.”

There, then, is my handy household tip for you newbie house holders, any and all genders.

There’s more in my new cookbook, Mike’s Cooking with Power Tools.

It’s the follow up to Tenderizing Tenderloin with an Impact Wrench, and of course the very popular Preparing your Favourite Desserts with a Welding Torch.

You can pick up a copy at most bookstores around town. Or at Mitre 10, near the hammers.

-

The story can now be told.

I have worn tights, stockings, pantyhose… I wore them, and I wore them on television so all could see. So, now it’s all out there.

I wasn’t all out there, if that’s where your mind went. It was 1970-something and I was younger and sufficiently svelte to, um, display said stockings, pantyhose, without revealing much of anything else.

Long story, short. (sorry) A well-established hosiery manufacturer, doesn’t matter who, was trialling what it described as pantyhose for men.

Manihose… that was the name. Please stop giggling. As the selling point was that Manihose brought warmth to the wearer, they were being field-tested in Tasmania, considered the coldest bit of antipodean real estate.

Somehow, a pair of Manihose found its way to the commercial TV current affairs show on which I was a cameraman. Yes. We made actual programs back then. And yes, yes. I got the job. Thanks for asking.

Basically, I needed to pull them over my underwear, and stand front of one of the silver-grey Marconi cameras we used. The Manihose were blue, and the underwear orange. You’ve got the picture.

The trick was not to move. At all.

For reasons of decency and the protection of family values nationwide – I am not making this up – broadcasting codes at the time precluded underwear models from moving. If we recorded ads for underwear, we’d use still photographs.

The TV presenter took a minute to explain why such a display warranted the public’s attention and showed his audience a brief-ish glimpse of my lower half, blue with an undercurrent of orange.

He, the presenter, was graceful and amusing, and absolutely nothing happened.

Now, you know that fame has been ignited by smaller things, careers kicked into gear in moments of serendipity. Wasn’t Mark Wahlberg propelled into moviedom from Calvin Klein’s underwear department?

It was not to be, not for me. In truth, I gave it no thought whatsoever. I had to get back to work, pronto.

There wasn’t even time to shed the tights; I zipped up my jeans over the Manihose and plunged into the rest of the day’s production schedule.

It was later, much later, that things went sideways.

I was on my way home. Changing buses in the city centre, I found myself in urgent need of a pee, so I ducked into the nearest toilets.

Here, in the utilitarian confines of a public facility, pressed by the schedule of the Number 46 bus and caught by nature’s call, I came to grasp the inevitable future failure of the Manihose brand.

There is no fly in stockings, pantyhose or Manihose. Yet men have need of a fly… it’s an anatomical necessity.

In the circumstances, I took matters into my own hands (sorry) and peeled my jeans down my knees, followed the Wranglers with the Manihose, and finally the orange underwear. I was now free to pee.

(Yes, women have to go through this ridiculous routine multiple times a day for their entire lives.)

In case you haven’t stood at a public urinal, it is commonly a stainless steel trough designed to accommodate perhaps six gentlemen.

Let me add another pictorial element: the toilets are a block from the harbour, off which regularly arrives a cold ‘sea breeze’, now whistling around my naked nethers.

It was about this moment when – and there’s no easy way to say this, but it is an accurate recounting – when approximately eight Japanese fishermen entered the public toilet.

I say approximately because I was not in any position to do a full count. I was facing the other way, so a quick glance had to suffice.

The clearest part of my recollection of that glance was that a couple of them were smiling.

Broadly. Big, big smiles.

This harbour town into which they had arrived was clearly welcoming of sailors, so went the conversation in my head. How long had these guys been at sea? Did I speak Japanese?

But this wasn’t the time for conversation. It was time for action, to do what every man would do in such circumstances…

I did just that, grabbing my underwear, jeans and hose, reefing them skywards, somehow simultaneously turning and fleeing the public toilets and shortly thereafter, the city.

The fly-free item, blue of colour, was disposed of not long after that. I have come to presume that field-testing of the Manihose product elsewhere, on other males across the antipodean landscape, also drew a negative response.

We made the point that Manihose simply would not fly. A note of thanks, then, to this (largely) unknown brotherhood.

Between us, we saved the world from another half-cocked consumer product.

You’re welcome.

-

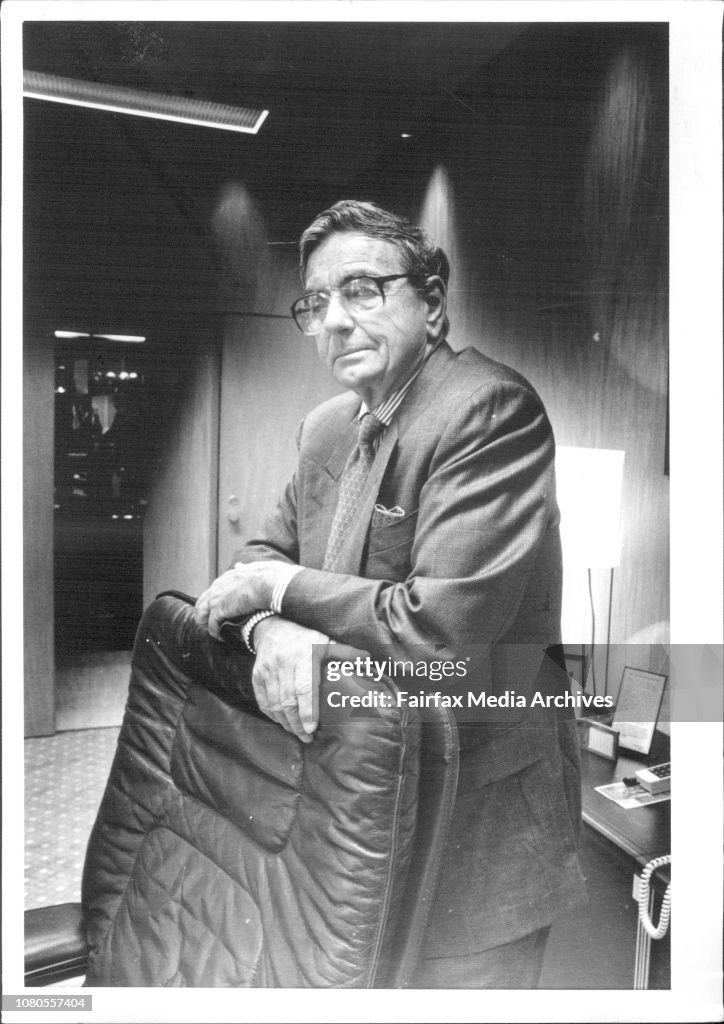

WAK: Robert Johnson

Johnston came to Detroit in May of 1995 to officiate at the opening of a new Austrade office. He was the ideal choice: a former chairman of Toyota Australia, and well known across the automotive sector worldwide, he was now chair of the Australian Trade Commission.

And Austrade was in expansionist mode. The recently appointed Executive General Manager for the Americas, Alex Stuart, had been brought out of the private sector (McKinsey & Company) to bring commercial smarts to a government agency.

Among the structural changes driven by Stuart was a reorganisation of the agency’s business expertise across the US and South America.

Promoting Australia’s maritime export interests went to a Houston office, food and consumer goods to New York, film/TV and market research to Los Angeles (also Stuart’s HQ) and the burgeoning automotive sector, of course, to Detroit.

(The final element of that strategy, an office dedicated to the IT and computer sector, saw the opening of an Austrade office in Silicon Valley a few months later.)

The Detroit office, in an office tower overlooking one of the city’s many Ford plants, had a high-tech image of planet Earth installed over its entranceway. It was to be run by a former senior executive from Chrysler that Stuart had recruited.

(I was there at Stuart’s request. He’d hired me a year earlier to handle Austrade’s communications, wherever needed across the Americas, and we worked closely together. It was a contractual arrangement that continued into the early 2000s.

On this occasion, I focussed on getting the US automotive trade press interested in the story of Austrade, Australia’s principal driver of exports, opening for business in Detroit, so invited them and briefed them on the event.)

Johnston’s arrival in Detroit, although planned, was a surprise in one core aspect. He was in a wheelchair, not something Austrade’s management in Sydney had told us to prepare for.

Johnston kind-of explained this quietly to me a little later: he’d had his hip joints replaced two days earlier, not long before getting on the plane to the US. It was likely, I surmised, that nobody at Austrade even knew he was getting on an international flight with his joints still fresh out of the box.

It mattered not. Robert Johnston handled the opening, the ribbon cutting, the speech making, the glad-handing and the interactions with aplomb, and more, a large smile on his face. He knew what he was doing. And if was feeling pain or any discomfort, he did not show it.

Afterwards, for reasons probably related to the fact I was also booked on a flight (mine back to Los Angeles) that I got the job of taking Robert Johnston to his plane at Detroit Airport and the next leg of his US trip.

Mr Johnston was moving out of Austrade mode and into that of a private citizen, now going to join old buddies – automotive industry associates – in Houston.

They were going to play golf. And this was made plain by the fact Mr Johnston had his golf bag across the handles of his wheelchair as we traversed the innards of Detroit Airport.

For those unfamiliar with this particular facility, it is several miles of concourses, walkways, tunnels, passages and sudden turns to the right.

We – Robert Johnston in the chair and me pushing – made good time. There’s a lot to be said for the command and control of a man in a wheelchair with a full set of golfclubs across its steel handles.

We were close to the aircraft gate when I ventured a question of a man now freed from his official responsibilities and looking forward to a few rounds in Houston.

Eyeing the golf clubs, I asked: “Mr Johnston? Tell me: what’s your handicap?”

Johnston didn’t hesitate. He half-turned towards me and answered, clearly and with wicked glint in his eye, “My fucking legs don’t work!”

I don’t remember actually getting him onto the aircraft, but I’m confident he made it on time. I may well have still been laughing at the joke he’d made at his own expense. He had the timing of a pro.

The story should end there, but it doesn’t. I caught my own flight home to Los Angeles, and then drove to Santa Paula where I lived in a cottage with my wife and three children. The phone calls started immediately.

“Did you take Mr Johnston to the airport?” asked the first caller. “did he catch his plane?”

“We can’t seem to find Mr Johnston,” said the next voice, from higher up in Austrade management. “That’s why we’re checking that he made it to the plane okay.”

The phone line between Austrade in Sydney and a little house about 75 miles northwest of Los Angeles was suddenly running hot. I assured them we, Mr Johnston and I, had reached the gate at Detroit Airport in plenty of time.

The phone calls from Sydney continued. Finally, one of the voices said: “We’ve found him at his hotel in Houston.”

“Thank heavens,” I said.

“He’s dead,” the voice added. Holy hell.

The phone calls moved further upstairs. “Can you tell me how was

Mr Johnston’s mood? Was everything …?”

I was now getting phone calls from a Parliamentary office. “Look, Mr Kerr. We’re about to go into the House, and we need to make a statement, say something about Mr Johnston and his work for Austrade.

“So how was he when you last saw him? What was his mood? How did he look to you?”

And then: “What did you talk about? His last words?”

I took a deep breath. Wow, I thought. Robert Johnston’s last words…

I decided in that moment that discretion was the better part of valour, and if that meant misleading the Australian Parliament, so be it. This was not the moment for disclosing Johnston’s wicked sense of humour.

“Mr Johnston was in a good mood,” I said, sticking to a kind of impromptu script. “He was in his wheelchair, yes, but didn’t appear to be in any pain. And he was looking forward to playing golf in Houston, seeing old friends.”

The 180-word speech to the Parliament about Johnston – made by the prime minister, Paul Keating, on May 8 of 1995 – hit all the right notes. Johnston, he pointed out, worked tirelessly and despite illness to push Australia towards exports. He was a true captain of industry, to use an old-fashioned term.

I learned later from Austrade management that it was believed likely that Robert Johnston had died as a result of some kind of post-surgical complication. Robert Johnston’s legs did not work, as he said, and in fact were working against him.

As Dr Chris Cunneen’s entry about Johnston in the Australian Dictionary of Biography notes that he’d faced down illness, including several cancers, such as brain cancer in early 1995, just weeks prior.

The biographer also notes that Johnston had lost an eye as a result, and wore an eye patch for some time. He was, added Dr Cunneen, “soon back at work.”

At the time of his death in the United States, Robert Johnston was doing what he’d always done in the face of his health issues. He toughed it out and got the job done.

So why tell this story now, 29 years after the very distant death of Robert Johnston, AO?

Dr Cunneen, his biographer from Macquarie University, recently noted that he had few sources from which to draw information about Robert Johnston, who had long since divorced and was childless.

For my own part, this is an unknown story about one of the captains of Australian industry. Ours was a brief encounter, but telling.

More, as a participant, I believe any family members – Dr Cunneen notes a nephew and a niece – ought to be given the option of learning a little more about Johnston.

Finally, it’s a damn fine story about a damn fine man, and should be told.

-

Brought home a bag of potatoes this week. Washed potatoes, $6.99 for ten kilos.

A great price, right? A damn good buy. I don’t get a whole lot of those, because let’s be honest, I’m male and I just want to be in and out of the supermarket as soon as humanly – manly? – possible. I really have no idea what I’m doing.

But then my brain says maybe, just maybe, these potatoes are not such a good deal. Maybe there’s a reason they’re so cheap, that there’s a reason they are not in transparent plastic, but hidden away in one of those big heavy paper bags.

You really can’t see what you’re getting until you’ve already paid for them. And now they’re yours, and you’re taking them home.

This brings to mind that bad date, back … then. From the beginning, you were just not sure about things, right? It was all mystery and maybes. What is under there? you asked yourself. What have I missed?

But the time of the, um, unveiling, then it’s too late. And like that date, you’ve got your hands on them now, and you bring them out into the light…

Holy shit, these are some ugly potatoes.

I gotta tell you, these are Igor potatoes. Even washed, they’ve got lumps in weird places, on the back, on the side. Lumps and bumps. There’s clumps of lumps on the bumps on these potatoes.

And they’ve got weird dark areas that look, let’s be honest, like some kind of disease.

I mean, maybe those dark little spots are just under the skin, but maybe it goes right through the whole potato. Remember, beauty is skin deep, but ugly goes right to the core.

I think we’re going to have cut deep here, Doctor Frankenstein. Hand me the scalpel.

Even the okay ones, they’ve got that slightly green tinge, like something that’s been long buried and now brought up from under the ground. There’s a whole horror movie thing going on here. It Came From Under Ground!

Even the good looking potatoes are starting to look pretty strange. They’re got little crevices between oddly symmetrical halves. It’s a bum. Now we’ve got bumps, clumps, lumps, rumps.

In fact, it’s got protuberances, swellings, bulges, protrusions, knobby bits. This potato looks like it was designed by one of those modern artists for whom two breasts and two buttocks and two knees wasn’t enough.

And this one I’m holding now, it’s short and rounded and scrubbed bare. Pale, unhealthy colour. Pretty much as wide as it is tall…

Holy hell! It’s my mother in law, that time I inadvertently walked in on her in the bath.

Remember that? It was a moment, an image burned into the psyche, something that’s gonna stick with you like chewing gum to the cat.

I tell you this, people, because this is why we cut potatoes into really small pieces and toss them into boiling water, a hot pre-heated oven or really, really hot fat.

We need to burn that memory – those arses and naked flesh and dark little crevices and diseases and mothers in law – right out of our heads.

Boil it, fry it, sear it, mash it! Doesn’t matter... just do it! Scorch it. Nuke it into oblivion.

Oh, and next time, buy your potatoes in see-thru bags…

p.s. Sorry about that mental picture I’ve left you with.

That was it.

The key now comes with a fob that’s the electronic boss, complete with its own chips and codes, even its own energy source.

Indeed, Captain Fob is the centre of an entire automotive universe, in command of something called the RF Transponder, and with that, everything from the car engine to lights and locks.

This brave new world is a radically different place from that which faced a young Kerr starting out on Life’s Voyage sometime in a previous century.

Back then, a missing car key was a minor inconvenience, a delay of perhaps minutes. We had long learned how to get a vehicle in motion entirely without a key.

It was a practical demonstration of necessity being the mother of invention.

For instance, my mother’s car was a necessity. If her key wasn’t available to me or my brother at the time of our intended journey – hard to believe, I know – we invented with wire and pliers.

The pair of us took to hotwiring cars like a politician to perks. In fact, mum’s car was needed for the borrowing so often that we installed a private, permanent hotwire – with a switch built in ! – between battery and starter motor.

The wire worked fine until one afternoon fire ignited the engine bay, and car became carbeque. True story. It was my brother’s fault.

But back to the current dilemma. I am key-less. And in this new world, Captain Fob at the helm, I am mere mug mechanic. I can gain access to the engine compartment, maybe even find the starter motor.

But can I still affix a wire to its nethers? What’s the likelihood my simple action will carbonize some sensitive (that is to say, expensive) component of that computer-controlled apparatus at the front of the vehicle?

Let’s remember how much it cost to repair my last automotive ‘repair.’

And let’s remember that a replacement key and electronic fob will be $300-plus, which was more than the entire price of my first car. And that key came free.

Right now, I really do need the current keys for the car. Wife’s bag? Never, ever a good idea. Could be bears, witches, giants in there.

Then there’s the No-Man’s-Land that is her side of the bed, not to mention the Don’t-Go-There recesses of the couch, among the half-finished, part-eaten and once-loved.

It’s even possible the car keys have made it to the very edge of the Kerr domestic universe, the eighth Circle of Hell that is our laundry.

What I need – what we all need – is a device, a TV-remote type gizmo that finds car keys by sending a signal to the key’s electronic bits.

There’ll be a beep, a blip, a burp… something to tells me where the keys are. Surely, such a thing could be included in the next generation of mobile phones? Find the key-finder app on the screen, press the virtual button, and presto!

Of course, before I can find my keys, first I’ll have to find my phone.

-

Austin 1800: Actually my dad’s car, borrowed once to haul a trailer. When the long load on that trailer shifted backwards, it lifted the ball of the trailer and the rear wheels of the Austin with it. (Think of a seesaw in motion but at 70 kays.) I was too busy tightening my sphincter to consider what an odd inverted-V we formed on that highway.

Austin Healey Sprite: This tiny sweetheart had a fold-down top, a feature so exciting it required every bit of bandwidth my 20-yo brain could muster. But an early sex lesson: It is not possible to traverse the transmission hump, no matter how damn fine the girl looks on the far side.

Cadillac CTS: This is the one that brought Cadillac back from the dead. Mine-for-a-moment was supercharged and even warming the tires was an adrenalin rush. 100 mph by the time we hit the top of the on-ramp. Sorry not sorry.

Chevrolet Silverado truck: 6-seater cab, 5.4 liter V8 and a full 4x8 bed that moved an entire household. It was so long, the chassis set up a kind of rhythmic lollop as it went down the highway. Damn I miss that truck.

Ford Bronco ll: Bought new and driven across Rockies, eventually the one-two punch of a sudden rain and a freeway K-rail reshaped the entire left side and left the driver badly shaken. It became the classic trade-in: bashed to fit and painted to match.

Ford Fair-something: Another lesson. Don’t buy the loaner car from your mechanic, even if you like the guy. It’s been driven at speed in reverse across the Nullabor, then the tank topped up by garden hose. After that, the shit was kicked out of it.

Ford Fair-something (2) A handsome wagon, far more recent than the above model, and served us well. But thirsty! Holy hell! This car needed a drink between drinks.

Ford Taurus wagon: This was a complete dog, even with consular plates. They may be diplomats but they’ll screw you like anybody else trying to flog a vehicle.

Honda Accord: The best of the Japanese stuff, and one we’d still be driving it if my wife looked at the warning lights on the dashboard occasionally. It’s true: she actually burned out the bulb in the ‘low fuel’ light.

Jaguar E-Type: (1967, S1) Bought in a California thrift store – a charity shop with car section – for $5500. Loved it and still writing about it. My wife called it the ‘blonde in the driveway.’ I just called it ‘mine.’

Jaguar XKR. (above) Got to play in one of these 5-litre supercharged beasts on a racetrack. A tip: five laps is not enough to get fully familiar with car or track, so get ten laps and find where the edges (esp. yours) really are.

Karmann Ghia: a Volkswagen, really, but low slung and belonging to my mother. My brother and I needed to ‘borrow’ this car so often we installed a permanent hot wire from the battery. Saves looking for a key. Or asking for permission.

Kia Carnival: Yes, it’s got seven seats, and along with the rest of the car, it’s made by circus clowns in Korea. It managed a whole 170 thousand kays on no fewer than three brand new engines before I finally gave up.

Land Rover SWB. A great bush-basher, equipped with a mechanical accelerator and doubtful brakes. But what are those half-inch steel bumpers for, anyway?

Mazda 929 wagon: A lesson in how Japanese cars are brilliantly planned and executed. This one moved a little family and two Dobermans halfway across the country. Gone now but never forgotten.

Mercedes 300TD: Oh, the turbo-diesel is a gem. A $2400 car that brought a $2800 insurance payout after a smash. The car was mostly unhurt, so for more insurance cash we considered going out and picking fights with other cars.

Mercedes 300 SEL: Elegant S series sedan with so much space in back that small kicky legs cannot reach the rear of the driver’s seat. Such a joy! But hold your breath until all the engine-check lights go out after ignition, ‘cos that’s $600 per flicker. No, $700.

Mini: Yellow like Woodstock in Charlie Brown and my first new car. So loved I sang happy birthday to it at 1,000 miles on the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Mitsubishi Magna: Utterly forgettable. Might have been white.

Nissan EXA Turbo: Miniscule weight + 1500 cc + a screaming turbo = serious fun. I actually approached this thing, the first time, with some trepidation. That lasted, oh, almost into the minutes.

Subaru Forester: A recent addition to the fleet, and I’m regretting being so late to the AWD party. The Subie always feels solid, sure, manoeuvrable. Sorry to sound like an ad, but this little white wagon runs and runs and runs, even after 300,000 kays. Two more Subies now decorate the drive.

Toyota Landcruiser truck: Teaching-a-16-year-old-to-drive-proof. And that 4.5 liter six engine easily hauls a tonne and its own weight. Love it to death, although I admit it’s overkill to use a two tonne go-anywhere vehicle to charge a 172 gram phone. Just sayin’

Triumph Herald: When you need an oil change, employ someone who knows what they’re doing. Hint: It isn’t you. Don’t take the roof off (even though it’s doable), because the entire car will bend at the doors. And then there’s that weird sideways leaf spring between the back wheels…

Volvo 240: The red beast cost all of a grand, but rendered pretty much the same sum at departure. Inside, number one child learned to drive manual and the basics of how to look after a car. There’s always space in my driveway for one of these.

Volvo 960 Wagon: Leather seats, electric everything and a brilliant alloy 3-liter six that made Los Angeles freeways bearable, even fun. It can join the 240 in the driveway any time.

-

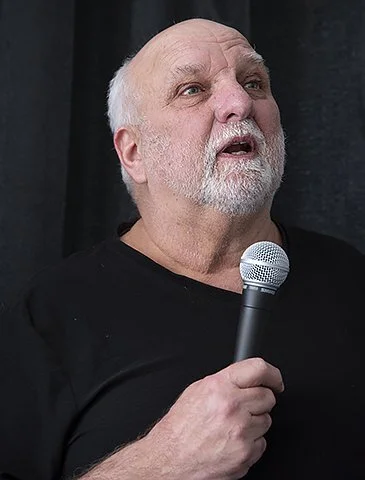

Turns out we’ve had it wrong about eggs and sperm. Well, not wrong, but we didn’t get the detail quite right.

We thought it was the fastest swimmer who got to the egg and did the job.

Not exactly. Turns out Mr. Successful is getting some help. Her egg is choosing the sperm and then giving him a leg up, as it were. (As opposed to a leg over, which we will get to in a minute.)

New research by really clever Swedish and English scientists shows eggs are selecting sperm by using little chemical attractants. Think of it like perfume, but on the molecular level.

The egg is actually drawn to the quality of the sperm. And it lets that selected sperm know it should swim faster and straighter.

Fast and straight, ‘cos that’s what the egg wants. Just saying! This is biology, folks. No political correctness going on down here.

And here’s something else the Swedish and English guys found. By the time of the choosing – that’s what it’s called in scientific circles: the choosing – there’s actually only about 250 sperm in the vicinity.

But let’s start this at the beginning. I know when comes to sex, you guys don’t like to rush things.

The beginnings are not only right there in the biology, but right here in this room tonight, this very comedy club.

It turns out -- this is a bit of a shock, so I hope you’re sitting comfortably --

It turns out that women don’t have to be very picky.

Because the actual choosing, genetically speaking, is not being made here in this very comedy club.

No sir! Let me explain…

There are two choosings. Yes, the first one is here, in this place where we are tonight. Hopefully a bar with a good selection of gin.

But here’s the weird science. It is only after the deed is done, the sex is had, the roll in the hay is over, the hanky panky complete, the bonking ended, the sausage hidden …

You guys may know some other scientific terms…

It is only then does the real work begin, the far more sophisticated process of the second choosing.

It is only after he’s rolled over, the female in the equation starts looking for desirable characteristics. He’s wondering what’s for breakfast but on the other side of the Sheridan, part two is already under way.

Let’s pause in this scientific exploration for a moment so I can break it down for you. During sex, a man sends an average 100 million sperm off to get her pregnant, to carry on the human race with his particular characteristics.

(And for some of us, it may be as many as 1.2 billion sperm per encounter, but this is not something the “some of us” should talk about. We are enormously modest about our enormous … fertility.)

But even a hundred million sperm. We are seriously going for quantity here, aren't we, men?

It’s the old male thing. And young male. When you don’t know what you’re doing, send lots. Everything you’ve got. One of them’s got to get lucky, right?

But the woman, she's got just one egg. Just one ovulating, receptive, yes-we-are-open-for-business egg. (let’s put the twin thing aside for now.)

One egg. So she gets to be choosy. She is going for quality here, not quantity.

But as I said, by the time of the actual choosing, we are already down to some 250 sperm. I know, I know … but we will get to the other guys later, trust me.

Now it’s come to chemistry, if you want to get precise. (Yeah, there’s chemistry between you, but it ain’t in the way you were thinking.)

So, chemistry. She has little receptors that can pick orange hair and roaming hands at 40 paces.

You, with the red hair and freckles over there, you’re dead to me. Mr. Buck Teeth, gone. Hello handsome with the receding chin and bad posture in the back. And goodbye.

On the other side of the Sheridan, she is giving her selected Mr. Right the inside track. Fast and straight, remember?

And even more interesting: to the also-rans of the 250 sperm that did make the journey, the Not Mr. Rights, the egg is telling them to swim slower.

She’s saying: Nah, take your time. Hitchhike, take a walk. Maybe you can catch an Uber. It’s all good. Bye. Call your mum!

As for the rest of the 100 million, well, I’m sorry to break it to you… they didn’t make it. I don’t know what happened.

Nobody has surveyed them to find out what went wrong. Gotta consider they are male, so they probably didn’t bring maps, didn’t think to ask for directions. Thought they may as well go back to the bar.

But it’s a reasonable question, right? What happened to the 100 million, minus 250, that didn’t go the distance?

I think that’s a research task for some guys whose work is done now and really could use the job.

Like, you know, a couple of really smart English and Swedish scientists?

-

The problem with speeding, of course, is that it’s not just about speed, any more than automobiles are just about mobility. A motor vehicle is about emotion as well as motion, sport as much as transport, and empowerment way beyond mere power.

When it comes to getting your personal motor running, cars rule.

The driver’s seat is our first real taste of the raw stuff, the heady whiff of command and control. And it’s ours from the moment that the old man gives us the okay to “get the car out” or “warm the engine” or some similar pretext. We’ve just been given the key to the door of the family wagon, to the ignition, and to life.

We lurch the beast down the driveway and out onto the tarmac, as we launch ourselves into the world. It’s a buzz, a rush, an entirely new variety of kick in the pants.

A couple of days later, that buzz gets an added boost when we lurch down the driveway after the old man has said nothing of the kind. And wasn’t even home when he didn’t say it.

From that initial thrill ride, cars quickly became something else again. About freedom from public transport, and better yet, from parents. The freedom to go wherever, whenever and whyever. The freedom to be free.

Once you own a car – well, that kicks in life’s turbocharger. Now you’ve got independence and privacy, as well as a room with a changing view. And it’s yours, somewhere to keep your stuff that’s not in your parents’ home, somewhere to take girls that your brother isn’t. He can’t snicker outside a door that’s zipping down the highway.

Now, we’re the front seat supremo. We call the shots, select speed and determine direction and destination. We decide who’s going, and who’s going nowhere. We are masters of the metal, of the music, of the drive-up menu. Hell, we’re masters of the universe.

For me, that door to liberty came in the unlikely form of a Morris Minor, an utterly inoffensive ladybug of a car that might have had three horsepower under the bonnet. The Minor was the Pride and Joy of the mother of my friend Jim. We, of course, were minors too, but much lower on the P and J scale.

Jim and Mike’s outings, unauthorized every one of them, began with some serious sphincter-tightening as we coasted that little four-seater out of his mum’s driveway. We’d engage just the starter motor (ask a mechanic) until we were part way down the street, and then those three horses could be quietly conscripted and our flight gain some speed.

Away and down that hill, Jim at the helm of our getaway vehicle, our grins widened with each passing driveway and then passing streets, and ultimately, swelled into pure elation when the last shackles of suburbia were shed.

We had escaped. We were free. Better yet, we’d taken charge of our own lives. For the first time, there was a gut-deep sense that we had control. It wasn’t about speed, but mobility. Direction mattered little, just as long as we were leaving that place of our childhood confinement.

For a couple of small-town boys, the vehicle’s power was not that of cubic centimetres, but the fact that it got us out of there.

The Morris, it can be admitted now, came close to taking out a couple of guideposts on the never-ending S-bend that was our coastal highway. This is what happens when teenagers get into an arm-wrestling competition with 1940s British automotive technology.

Cars have changed, but youth hasn’t. It’s still a squirming package of bad hair and worse skin fueled by testosterone (and estrogen), stimulated by risk-taking and exuberance, nagged by inexperience, bored with boredom and driven to be impulsive. And this is the time of their lives – at this cresting peak of their biological, chemical and physical tides – that we put them behind the wheel and give them their first real taste of power.

As Jim’s mum thought when she put the Morris away at night: What could possibly go wrong? -

I’ve been doing that country thing last couple of weeks, clearing up and burning off around my house, the dry stuff now on the ground before it becomes some kind of fire hazard.

My place, for the record, is way down south. The street is called Van Morey, and it’s in a place called Margate, like the English town Margate, but absolutely nothing like the English town Margate.

Good thing, right, this clearing up all the forest litter?

Yes, it is, except I keep seeing snakes everywhere. Everything I lift up, there’s another pair of beady little eyes watching me, tongue flicking, poison glands working overtime.

Snakes. I’ve always hated them, cold slimy things -- primitive, dangerous.

Now, normally I call my wife so she can take care of the problem.

She just strides in there, snapping a forked branch off a tree as she goes, ready to pin the little bastard to the ground.

Barefooted, bare-armed. No matter to her. Next thing I know, that snake is in some kind of bag (could be my pillow case but I’m not arguing here) and is shoved into the fridge for a little while, so it gets real slow.

Then she takes it off somewhere to join its family, or the circus or something. I don’t know, and I don’t want to know. I’m just looking out to make sure she hasn’t got a forked stick anywhere near me, specially if we’re having an argument.

Anyway…. On this particular day, my wife is not around.

I have to call the these removalist guys. They call themselves Reptile Rescue. You know about these people? For 20 bucks a head — ten per fang -- they come take care of your problem.

So I’ve got the guy on the phone. I ask all the usual questions, tell him I’ve got a real issue, never seen so many snakes.

Earliest I can get there is next week at the earliest, he says. I picked up 25 this week alone.

Twenty five?!! Okay, okay, I say. That will have to do.

So now I’ve got you there on the phone, I ask the reptile rescue man, what do you do with the snakes?

Well, they’re a very important part of the food chain around here, he says.

I completely misunderstand this. Completely.

You eat them?

No, no, no. They’re a real important in nature, circle of life, all that stuff. So we relocate them, take them into the forest well away from where we find them.

I’ve got a nice spot off the road, he continues. Bit of a creek there for water. It’s five kilometres up Van Morey Road in Margate, and that’s where I let them go.

Ah-ha… Good to know.

Now it’s his turn to ask me a question.

He says, where are these little bastards? Where is this place of yours? Am I going to have problem finding it, because these places in the back blocks …

No, no, no. I say. No, sir. You’ll have no problem at all.

My place is a nice little spot there, right beside the road, five kilometres up Van Morey Road, in Margate.

You baaaaaaaaaaaaastard!

-

It turns out that God does not favour any particular religion. Not Anglican or Presbyterian.

Nor any race: God is not Australian nor American nor an Englishman.

God is not a Republican, either. Neither Asian nor Caucasian. No, in the big scheme of things, of all the ‘an’ words, it turns out God is … a comedian.

How else do you explain an entity that would design a human being, deliberately make us funny looking and consider that to be some kind of natural contraceptive?

If that’s not enough joking around, God gave us alcohol, which pretty much guaranteed we’d have generation after generation of funny looking people.

I mean, look around the room here, look at the person you came with, and tell me that’s not true.

God is pissing himself laughing, right now, about that little joke.

I should say: pissing herself laughing. God is clearly a woman and not only that, she favours her own sex.

The evidence is right there with Adam and Eve. Adam’s walking around, naked, going: So check this out. I’ve got one of these.

And Eve took a look and said yeah, and I’ve got one of these. And God says that with one of these, I can get one of those anytime I like.

I think that shows some serious favouritism.

I know what you’re saying: But if God is female, wouldn‘t she be a Goddess?

I can tell you this. Around our house, Goddess is a title reserved for my wife. This is a woman who agrees that it was God who created man, but given the opportunity, she would have done a whole lot better.

And certainly, during the actual creation of mankind, there were some mistakes.

I mean: men have nipples. What they hell is that about?

During the design phase, did God look at Eve and Adam in her big sketchbook and then stand back and go: Adam looks kind of weird without nipples, so she took out a giant marker and drew them on.

And then just couldn’t stop herself and drew on big eyebrows and then a little beard. You know how that goes …

And then she thought I’ll put a little beard on Eve too, except I’ll put it down here. Ha. Ha. Ha. Humans will laugh about this one day, trust me, she said.

Memo to self, she added. Invent Brazil.

To stay in the midsection for a moment, the area we think of as a fun zone, the playground or, if you’re one of those real estate people who understand local government planning regulations, it’s called a recreation area.

Are you with me here?

So what does God do then? Puts a toxic waste pipeline right through the middle of the recreation area. Now that’s real comedian at work.

Anyway, so with this giant packet of markers, God made people in a multitude of different colours, men and women, gay, straight. Different styles to suit different landscapes. It’s a design thing, you know?

She even made vegetarians and vegans – and made them out of meat. How funny is that! God, the original Lady Gag Gag.

All went fairly well, I think, with this creation process until she got to the commandments, the rules for human behaviour. Which frankly, turned out to be not worth the paper they’re not written on.

The commandments … rules written on bloody great blocks of stone. Not a moment’s thought given transportation, to distribution, sales and merchandising.

What about duplication, God’s favourite subject?. Try humping that stone tablet up onto the Xerox.

So, there’s one copy only, for all the human race. How did this go down with God’s creation?

Listen everybody, we’ve got the rules now from God. They’ve got the ox stuff in there, and the coveting, the neighbours … all ten rules. Everybody should come around and check out these commandments.

And you say: well, no, actually. I’m planning to get some alcohol into that funny looking girl next door tonight, so I’ll just wait for God’s rules to come out on blue ray. But thanks anyway.

Some people think God has had other communications with us, too, and that she’s going to send her son down here again. There’s already a movie being made about it: The title is: Christ Two, the Return.

I don’t think this is true. I think some people may have misheard God. What she actually said, like any parent hearing thumping noises, she stood at the top of the stairs and yelled: Christ almighty! Don’t make me come down there …

So aside from reproduction and alcohol … I’m sorry, I got that the wrong way around. It’s alcohol and then reproduction, isn’t it …

Aside from those, God gave us things to do while we’re here, some things to keep us busy. Little mysteries to figure out.

Some personal questions, like how many Os are there in orgasm?

Questions about the order of things, such as this: before can openers, how did cats know it was dinner time?

And finally, questions about the meaning of life, like who am I, why am I here and where the hell is my atm card?

-

I write in praise of duct tape.

Yes, duct tape. Not duck tape, although there’s a brand by that name, and certainly you wouldn’t be the first to get that right-wrong. And to be clear, duck tape made from and for actual ducks would be useless unless you knew a lot more about ducks than you currently do.

All that aside, it’s true that duct tape is one of life’s essentials, the core of a decent fix-it kit. If it moves and shouldn’t, use duct tape. If it doesn’t move and should, use WD40… So the maxim goes.

Good, practical advice. Add a decent hammer, like an Estwing, and you’ve got yourself the beginnings of a great repair slash tool collection. It’ll also keep those ducks in line.

Once you have discovered the stuff, its all-purpose-all-the-time sticky goodness, you’ll always want to have a roll close at hand. Well, maybe not in a pocket or purse: it bulges and the police are likely to assume you’re planning a kidnapping.

But a drawer, that one right under the knives and forks, is ideal. See? We’re already together on this.

Check your options – there is a duct tape made for actual ducts, for instance – and buy the expensive brand. You’ll thank me for it.

The story goes that duct tape was the idea of a Vesta Stoudt, a WWll ordnance factory worker and mother of two sailors, who suggested sealing ammunition boxes with a fabric tape that she’d tested herself.

I’ve read where people now claim it has 1001 uses. It’s certainly true that life is full of stuff that moves when it shouldn’t. Gravity’s good, but duct tape is better.

Want to prevent your clothes from gaping? Duct tape.

Summer flies driving you bananas? Ditto.

The lint filter not doing the whole job? Ditto. Ditto.

Need a temporary fix for that car radiator hose, loose exhaust, body panel or window? All of them, simultaneously? You got it.

It was duct tape that saved the astronauts on Apollo 13 and every spacecraft now carries a couple of rolls. Last year, a tiny hole in the International Space Station was patched with the stuff.

In fictional life, too. There was a major moment in the Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, when Blomquist saves Salander’s life by binding her head wounds with duct tape until the paramedics arrived.

Around the only-slightly-less-fictional Kerr house, duct tape keeps things together in a multiplicity of ways. It secures a plastic greenhouse that is threatening to disintegrate after successive batterings by westerlies.

There are bits of an otherwise indestructible Toyota truck in my driveway that are bonded by duct tape.

My lawnmower would have shaken itself into shattered, scattered shards of Chinese steel were it not for quantities of the stuff. The handle alone took a roll.

Innumerable cardboard boxes of ephemera from my years on this planet are held together with duct tape. They are in a shed that itself …. You get the idea.

Duct tape has been with me for the big moments in life. Sticky moments, you might call them.

It was there for those get-the-kid’s-lunch-together-in-the-seconds-before-the-bus-comes moments. In one hand was a burrito, left over from last night’s dinner. In the other was a pair of paper plates, left over from last night’s dinner.

But how to fold and seal the paper plates around the burrito so as to ensure its deliciousness (if not its heat) would hold up until noon, or whenever it is that schoolkids eat lunch? Surely one of life’s core questions, and yet inexplicably unanswered on MasterChef.

The answer, of course, was in that drawer below the knives and forks. The top plate inverted to form a flying saucer shape (extra Parent Points for that) and the burrito safely tucked inside. Then, the edges deftly closed with a quality duct tape.

Lunch is assigned, sealed and (frisbee-flick here!) delivered. Yes, dad has saved the day again.

And then there was my proudest moment, arriving not long after I became a grandfather.

The curly-headed one was without a nappy – a diaper if you prefer – late on a Sunday. Nobody wanted to make the long trek down the hill to find out if any place was open.

A thorough search eventually located a similar item, except built for a much larger person. A circus canvas when we needed a pup tent.

How to ..? Don’t jump ahead of me here.

Yes, there were multiple folds, tucks and rolls. But the final product was a work of art, the silver-grey tape contrasting cleverly with the padded white panty, altogether a neat fit on a beautiful baby butt. And to top it off, I encircled her waist and chubby little legs with a 50 mm strip of duct tape.

Nothing could provide a stronger, more leak-proof bond between underpant and flawless skin. Perfection.

Should have taken a photo, something to bring out when teenage hood arrives. Oh, well.

But you’ll be pleased to know the last of the duct tape sticky stuff should detach itself from that derriere any week now.

-

For best results, read it aloud.

Getting a job is one thing. Leaving it… well, that’s something else again.

When cowboys finish the job, they are deranged.

Priests, as you know, are defrocked.

Then there’s models, who are deposed. Some are deformed or defaced.

Those that model underwear are debriefed, or the opposite, denuded.

Which is better than movie stars, who are defamed.

Private eyes are detailed and spies debugged.

Tennis players defaulted, but it’s deserved, while skiers are declined.

Cricketers are decreased.

Lance Armstrong, by the way, was detoured.

Organ transport surgeons who once delivered are now departed.

Podiatrists simply suffer defeat.

Fishermen are debated.

Those heating, ventilation and air-conditioning guys are deducted.

But liars and cheats, they’re deployed.

Financiers, devalued. Miners deposited.

Sales guys, decommissioned and depreciated.

The worst fate awaits teachers, who are detested.

Bakers are defloured and clerical staff, worse, defiled.

Ten pin bowlers are just despaired.

All this is a bit depressing, which is what happens to drycleaners. Before they’re depleted.

Things are better for others. At the end, electricians are defused but truly delighted.

Baristas are, yes, decaffeinated, and their customers, deactivated.

Politicians are devoted, they’d like us to believe. But it’s just a device.

And clutterers don’t like it, but in the end, they are devoid.

Virgins are decoyed while hookers are just … delayed.

Musicians are decomposed of course.

Old musicians just become defunct.

Sewer workers are deterred.

As for Trump…He’s left a nation degraded, demeaned, debased

The appropriate ending is that he’s demobbed and debunked.

That’s democracy.

So there.

-

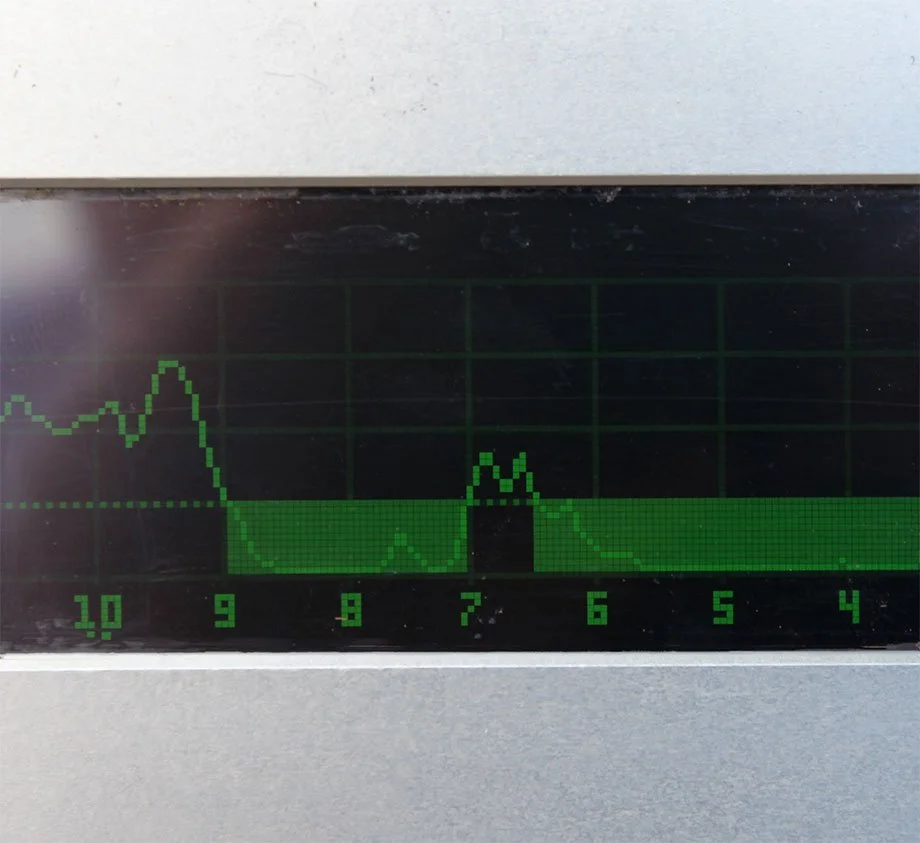

Michael Ryan takes the hammer from its hitch on his belt, and circles his subject while simultaneously dispensing a series of well-placed thwacks to the outermost epidermis.

He’s listening intently to what the blows reveal. Most often, they indicate solid, healthy internals, but occasionally – in that split second – the sound comes back hollow.

With that, it’s time to move to a more precise diagnostic tool. He reaches for a German-built device he’s been working with for about a year. The IML-RESI will render a digital readout of what’s going on inside the body in front of him.

It doesn’t provide a CT scan exactly, but a green squiggly line, much like that of a cardiac monitor. The subject of this scan is a power pole, and it’s talking to Michael Ryan. The news is not good.

On the screen, the green line has dipped into negative territory for some millimetres. What that means, says Ryan, is the IML device’s 3-mm drill bit has hit softer wood. “The pole is rotting from the inside out,” he says bluntly. “It’s well within specs, the thirty mm. of solid wood we need as a minimum, but this is one we’ll keep an eye on.”

Couldn’t that just be a crack in the timber? “No,” he says, pulling up another pole’s digital profile. “See how a crack has much briefer fall and rise on the graph?” Very different readout, very different reason.

Ryan is currently working through what’s called a package of some 400 power poles at Campania, just north of Richmond. He and a colleague Andrew Suffolk started some kilometres apart and are working their way towards each other.

“There’s reasons for working in pairs, mostly safety,” he says. “And sometimes it’s just useful having another pair of eyes looking at what you’re looking at.”

At the base of the pole is a series of black plastic plugs which cover 450 mm tunnels bored at roughly 60 degrees towards the base of the pole.

White sticks of fungicide are inserted into these shafts to keep natural rot at bay and maximise the integrity of the pole at ground-level. As part of his testing regimen, Ryan adds a fresh sticks to each, then replaces the plastic plug.

Michael Ryan came to this job ten years ago after a lengthy stay at Forestry Tasmania. “It’s similar work,” he says, “just that I’ve moved from dealing with live trees to working with dead ones.” He laughs.

One of nine asset inspectors TasNetworks employs in the south of Tasmania (with another 12 in the north) Ryan’s job is to evaluate the health of the company’s poles on a revolving basis. Each gets a thorough checkup every five years.

It’s no small job. Some 290,000 poles are subject to this testing regime.

And like a medical exam, a good deal of information is readily available in, and on, the body of the patient … but only if you know where to look.

A single pole offers up a significant amount of data, much of manifest on its exterior casing. A 40-mm circular medallion sunk into the wood offers what is essentially a birth certificate: it identifies the type of wood, its manufacturing date and the pole length.

A second metallic label identifies the pole by a unique number; TasNetworks knows every one of its poles by that integer, including its location and erection date. A third number, again attached to the outer casing, identifies the pole in sequence, on its own particular street.

Ryan’s attention now turns skyward. He’s looking at the cross arms, sections of hardwood on the outer ends of which are the wires and insulators. This is a process less dependent on clever engineering and a powerful Milwaukee cordless drill, and more on an experienced pair of eyes.

On this particular pole the arm is in need of replacement. A steel support strap has come loose from the wood, and sections of the upper edge are clearly weathered. He moves to record the defect on his Toughpad computer tablet, identifying the pole number and including a semi-close-up photo he’s shot with a tiny camera.

There’s one more job to do. He extracts a spirit level from his tool chest and checks the slant of the pole. This one is straight as a die, but anything beyond 7 degrees is going to get a notation and further scrutiny, possibly straightening or replacement.

The testing job complete, he closes off the job on the tablet. On the screen, a map of this section of Campania appears, each pole identified by a dot. One in a small sea of orange dots turns to green.

The whole process of checking the pole’s internal integrity, and critically, its expected lifespan, has taken perhaps minutes, but this one was straight forward. We move to the next, some 60 metres away.

Ryan’s diagnosis carries a good deal of weight. If necessary, replacement of a dangerously weakened pole could come as soon as 24 hours, a week if things are merely urgent, or 365 days if he considers it will last that long.

“Even an older pole should have at least five more years of life. A total of fifty years is a good span,” he adds.

As poles rot at the base, most obviously just below the soil, a standard technique is to brace it with a steel stake, a hefty V-shaped galvanized steel section that’s rammed deep into the earth beside the wood, then bolted through.

“A stake will add about fifteen years to a pole’s life,” he notes. “But the steel, too, needs to be checked for corrosion, especially here at the soil surface.” He uses the claw of the hammer to expose the base of the steel.

Similarly, square-section steel poles, used as intermediates between poles and homes, get a close examination. Any breakdown in the galvanized coating is reported.

A wood pole, despite its weakness through the natural process of decay, garners support from the chain of poles of which it’s a part, as well as brace poles (usually on the opposite side of the street) and the cabling that runs on the diagonal to nearby homes. They form a cross hatching of support, like multiple stays on a tent.

The pole’s is a humble but crucial task, keeping aloft massive braided aluminium wires, the top-most high tension strands carrying some 11,000 volts, and lower wires 415, after being stepped down by transformers. The cables delivering power to homes are reduced again to the familiar 240 volts.

We move to a new pole, one less than 10 years old. It’s already getting the once-over, beginning with a check with a test pen for any signs of leakage from the wires above. Even a wooden power pole can conduct electricity.

When Ryan is satisfied, he nails a new marker – a piece of rectangular steel plate – at head height, then from his pocket pulls a square-headed punch. With a succession of small blows, the numbers 11 and 19 appear on the plate.

Like a medical record, he’s documenting the date of the first in a regular history of checkups.

Then it’s back to the computer tablet, and at the touch of his fingertips, another orange dot turns green. Just 289,998 poles to go.

-

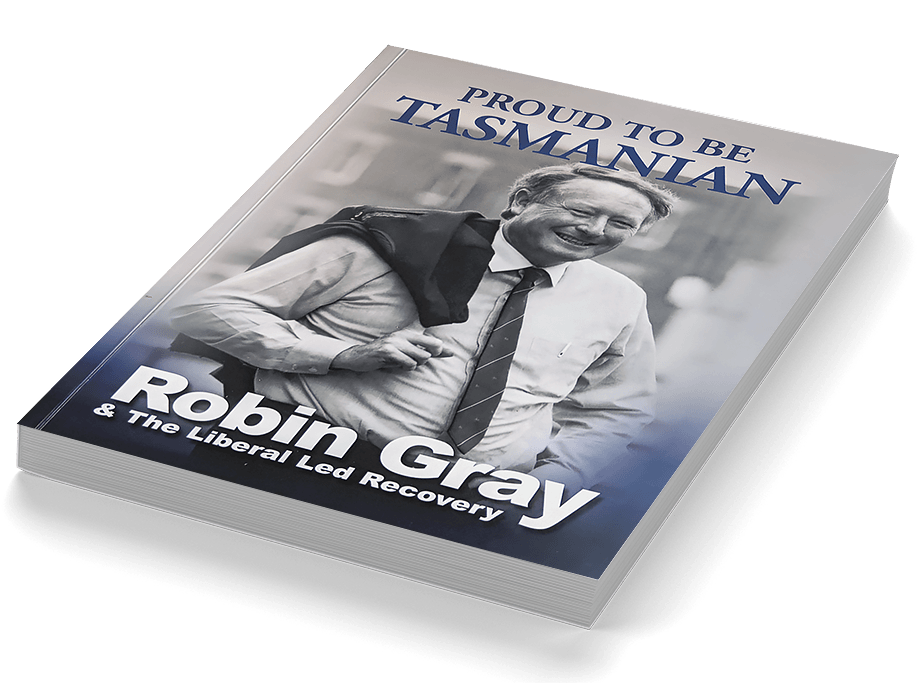

The thing about Robin Gray, the once-premier of Tasmania, is that he’s polarising. You like him or you don’t, and there’s not much space between. And he doesn’t care, either way.

His just-published book, written with former head of office, Andrew Tilt, cedes not a millimetre of that turf, nor the forests, rivers or any of the other terrain on which he chose to do battle.

Called ‘Proud to be Tasmanian – Robin Gray and the Liberal-Led Recovery’ – a campaign slogan if you ever heard one – it lays out Gray’s view of the wrongs of the world that was Tasmania in the early 1980s. And what he did to right them.

Aside from The Dam and The Mill – more on that later – Gray largely succeeded. This book is his determination that his legacy not be forgotten; its physical forms of ships and infrastructure, buildings and businesses underpin much of today’s Tasmania.

The book claims to ‘fill the gap in historical publications’, yet leaves unanswered large gaps in a reader’s understanding of Gray, the man and his motivations.

In fact, he was an enigma even to those who worked closely with him, a private man through a very public career.

Certainly, Gray knew what he wanted and worked himself hard, and those around him, to get it done. Where no governmental entity or program existed to complete the job, Gray found the necessary instruments. And sometimes they were blunt instruments.

That speaks to the character of the man. Over six feet, large of frame and deep of voice, he eschewed small talk and the hail-fellow-well-met niceties of elected officials. Gray was not a natural politician.

His pre-political life as an agricultural consultant meant travelling Tasmania, getting his hands in the dirt, speaking the language of country folks, usually direct and colourful. Canvassing for votes in Wilmot before the 1976 election, it was much the same – travel and face-to-face conversation.

His huge appetite for work, alone or with a small group of peers, made him a formidable opponent on the hustings and Parliament. Wilmot, largely rural and Tasmania’s largest electorate, understood Gray; he outpolled all three sitting Liberal members at his first try.

He had behind him a northern private sector long suspicious of a government concentrated in the south. More, he had what they call in politics a mongrel streak, a readiness to bite – and be bitten.

By late 1981, Gray’s right moment-right time arrived. Barely 40, he became Liberal leader just as his Labor opposition fell, listless and lazy after being in power (with one brief interlude) for four decades, weakened by internal knife-fights, lacking rudder, vision or will.

Labor’s death spiral revolved around whether or not to build a dam on the Gordon River below the Franklin. The dithering and delays became a confusion of alternatives in which upper and lower houses of Parliament actually promoted their own separate preference.

To those of us in the media, it was like watching a suicide in slow motion.

The final act, on November 11, 1981 (yes, Remembrance Day) was to replace a besieged Labor leader, the Premier Doug Lowe, with Harry Holgate, who’d long manoeuvred for the top job.

The rupture, clearly visible through its elected members, reflected Labor’s vulnerabilities to union power and internal enemies. Lowe was caught between a pro-dam union base and the party’s natural allies, a nascent but vocal constituency with an environmental bent.

Holgate’s was a desperate act and he knew it. At his 1981 Xmas party for the media, the new premier was clearly nervous about the upcoming election.

When I gave him, a little mischievously, a tube of superglue as a gift, he asked what it was for. I suggested he spread its contents on his chair, and then sit on it. “It may help you keep your seat,” I offered.

Holgate lost the Premiership to Gray on May 15, 1982. He’d held the position for barely six months.

(Curiously, Gray’s own replacement of Geoff Pearsall as Leader of the Liberal Party, just hours before Labor’s switch to Holgate that very same November, had been lost in the news shuffle.)

Now Gray was ready to rout enemies and right wrongs. It was time, to use an expression much used around the office by Gray and Tilt both, “to crash through – or crash.”

At his back were two superior politicians, Max Bingham and Geoff Pearsall; both of whom had recently led the party, both versed in Parliamentary manner and form. They were political bookends for a man who’d only been in the House for six years and Liberal leader for only as many months.

Bingham’s part, in particular, requires acknowledgement. An Oxford law graduate, Rhodes scholar, he was a QC and later headed the Criminal Justice Commission in Queensland. Attorney General in the Tasmanian Parliament, he brought dignity, warmth and a rare intelligence, even trading pithy Latin expressions with his staff.

Geoff Pearsall, meanwhile, had the smarts to organize the government business in the house, to keep the opposition wrong-footed. It was Pearsall’s reward for his time in opposition and he took almost a wicked pleasure in using his new clout.

In government, Gray was often accused of being autocratic. Perhaps, but only if measured against his predecessors: he was going to make decisions and stick with them. And he was unequivocally a supporter of Gordon below Franklin.

More, he determined to control the information flow; those in the loop were kept to a minimum.

In the media section I became one of three – plus a first-rate secretary – a quarter of Labor’s media people. Everything government did and said was channelled through us… hard work, when some days 20 news releases went out.

Briefings came from Ministers and senior staff; we were rarely privy to Cabinet documents and their carefully articulated arguments for and against proposals. Elsewhere we dealt with queries from the media, sometimes enlightening but mostly politics as usual.

Then, the premier’s entire staff was just a dozen people including two imported researchers. The small number worked to form a cohesive unit: on more than one occasion, we were all in a single room in Parliament, an office, even a restaurant. Gray was most comfortable keeping things close.

He knew every one of us, heard us, trusted us. After I persuaded him to mount a penny farthing at Evandale (the newspaper photo captions – Going, Going, Gone – told the eventual story well) he recovered and in the quiet of the car, raised one oil-stained trouser leg. “I know who’s paying the drycleaning for this,” he said.

Running this outfit was Andrew Tilt, a hard-hitting political journalist turned Gray’s head of office, gatekeeper, strategist, enforcer. Like Gray, Tilt used his vocal gruffness to advantage, another blunt instrument. As co-author of this book, he’s clearly softened little.

In part, the book is a regular late-life political reflection, a view of the how and why of major decisions, a recitation of annual state of the state speeches, a list of accomplishments. But like politicians all over, it is in Gray’s failures that the real insights should be sought.

Question: How does a small group of people (his estimate is 10% of the electorate) hijack the Gordon below Franklin dam debate, confound media and public alike, involve the Federal government, and get the decision of the Tasmanian people overturned?

For this movement, the Tasmanian Wilderness Society (TWS), new truths were created. It became the Franklin dam, (we’re stuck with it, even in Wikipedia) despite being on the Gordon. The Franklin was now “Australia’s last wild river,” a dubious claim at best. Stunts like sending rafters downriver were invented to grab media attention.

And in a moment of inspiration (that ought to be the lead paragraph of every pr handbook), the TWS set up headquarters at Strahan, as physically close to the proposed dam that telephone lines would stretch.

From there, the media – Australia and the world – got an uninterrupted briefing of what was going on. Just not from the people actually building the dam.

Gray’s failure was 300 kilometres away, back in Hobart. Yes, multiple other issues and Parliament required his close attention. Yes, he’d comprehensively defeated Labor on this very same dam question. Yes, he had support across the entire apparatus of government.