The New Queenstown

A MINING TOWN COMES TO A CROSSROADS

In Queenstown, the pieces are coming together.

Critical crusher units have been refurbished, new exploration drives developed and the tailings dam height has been raised. There’s a new treatment plant, drill rig, and a fleet of trucks.

There’s a new manager, Clint Mayes, in place. And on any one day, there are some thirty specialists at work here, drawn from mine sites across Australia and overseas.

They know where the ore bodies are buried. They know what they’re going to do.

It’s been six years, and Queenstown’s famous Mt. Lyell copper mine is set to re-open.

But it will open to a very different town, and a populace much altered by – and during – that interval.

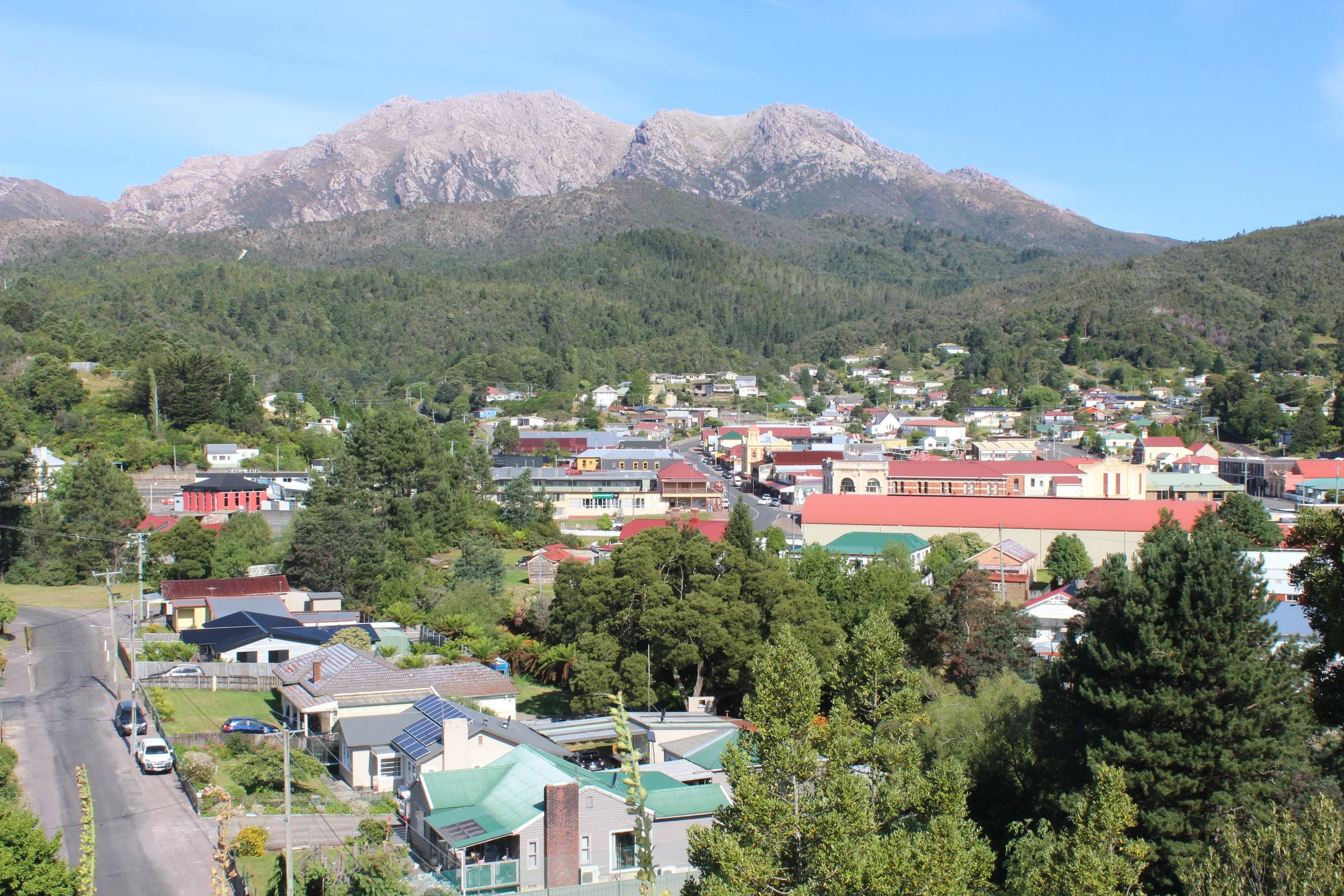

The evidence of change begins in the hills that surround the town. Once rock-raw, a lunar surface, Queenstown’s hills are now surprisingly green. Tailings dumps are still evident, but close in, native trees have sprung up.

Similarly, green shoots of a new economy, a new culture, have begun to take hold here. An environmental sensibility, another form of green, has also taken root. This is not the Queenstown of old.

Back then, Mt. Lyell Mining and Railway Company oversaw everything from men and machines to power and water supplies, scholarships to school lunches. But the days of the company town have gone too.

The decision about restarting the mine is now up to Copper Mines of Tasmania (CMT), part of India-based Vedanta Limited, the mine owner since 1998 and a major world copper producer.

And CMT’s decision will be driven largely by the copper price on the London Metal Exchange, 17,000 kms. from Queenstown. Copper is the third most traded metal after iron and aluminium; electric vehicle demand indicates the world will need 2.5 times current copper production within a decade.

CMT will first contract a mining services company to employ a new workforce. It will be smaller than that which walked out of here on July 19, 2014. Those newcomers will have to come from elsewhere; when skilled undergrounders left here to go wherever the work was, six years ago, they stayed away.

The mine will be a different proposition, too, with much of the hazardous work underground being done by remote-controlled machinery. This is the way mining is done today.

Even when the ‘go’ button is pressed, actual production will likely take a further 18 months’ work. The start-up costs for this giant project, including that already spent on care and maintenance, will come close to $200 million.

In 2020, there are some 1800 people in Queenstown, a third of the numbers of the town’s heyday. Many are retired, but for those working in tourism businesses, there’s a kind of electricity, the spark of potential across the town.

Joy Chappell is one of those invested in this new Queenstown, personally and professionally. She’s been here 16 years and is encouraged by the diversity in visitor offerings, from walking trips into the world heritage area to rafting trips, 100 people a time going down the Franklin River – and more on the King – in peak season.

She singles out a mountain bike trail slated for Mt. Owen, the massive outcrop that sits squarely in the town’s view. A design for a black diamond (a very tough) course is being prepared, along with one for beginners, funded to the tune of $2.5 million by the state government. West Coast Council and Parks and Wildlife are overseeing the design and build.

“Mountain biking will bring high-yield visitors, professionals looking for good food and accommodation, as well as quality services,” says the owner of Mt. Lyell Anchorage bed-and-breakfast.

Chappell and partner Anthony Coulson have also rejuvenated the 1933 Paragon Theatre as an art deco cinema-restaurant. The nightly big-screen showing, documentaries about the dams controversy of the 1980s, speaks to the greening of the town.

She also points to locally grown ventures: the Western Art Space, the studio of Raymond Arnold and Helena Demczuk that has proved a catalyst for an entire community of artists. Close by the Q Bank Gallery houses an eclectic art collection.

Even the local library is in on the act, displaying a long-lost necklace from Mt Lyell’s pioneering family, the Stichts.

October’s Unconformity, Queenstown’s three-day festival of visual arts, music, performance and dance, has just made it onto 2020’s list of the 40 coolest things to do on the planet, according to Time Out.

That’s some accolade in this town – or any.

“This new arts culture of Queenstown has made a significant impact,” says Chappell. “More, it’s changed perceptions of how people see us, how we see ourselves.”

At the same time, Queenstown is still grappling with its mining legacy issues, most obviously the tailings dumps and the pumpkin-orange scar known as the Queen River running the length of the town.

“Getting this cleaned up is critical,” says Anthony Coulson, a former mine maintenance supervisor. Although the old Mt. Lyell company had success in revegetating tailings dumps, little recent work has gone into covering or remediating the sulphidic waste left after a century of operation.

And local rainfall, an extraordinary 2400 mm annually, inevitably carries that waste into the river, causing the worst case of acid mine drainage in Australia. It’s not a picture that’s to be included in local tourism campaigns anytime soon.

Coulson and Chappell also run RoamWild Tours, taking guests 20 minutes away to Lake Margaret village and power station, built to power Mt. Lyell before there was a Hydro-Electric Commission. Anthony ran tours of the mine itself; three years ago, the then-manager closed them down.

Today, Coulson is more optimistic about tourism than mining. Even old miners, like John Halton, want to move on.

At Queenstown’s golf course, he’s mowing around the holes closest to the club house. It’s early 2020, but the first official golf day for 10 months. “Not enough members use the place,” he says of the club at the south end of town. “Private functions, birthdays and so on, would make a huge difference.”

Similar membership declines are reported across local community and sports groups, including the football club, famous for its gravel oval. There’s something familiar in this to Halton; as the mine’s HR manager, he was literally the last person out of the door.

This new Queenstown “needs to be tourism driven,” he says. “We’ve already come a long way, but at the same time, we need to find ways to clean up the residues from Mt. Lyell.

“And if the mine does reopen,” he considers, “miners will probably not live here but somewhere else,” he adds. “They’ll be fly in-fly out – FIFO – workers, one week on, one off. That’s the gig these days.”

Halton points out that the local high school principal and Queenstown’s police inspector both live in Tasmania’s northwest, and commute to work.

From its central perch overlooking the town, the original mine manager’s house, Penghana, has itself moved into the tourism industry. It’s now an upscale bed and breakfast in the care of Karen Nixon and Steve Berndt, a couple who moved from northern NSW to Queenstown.

Nixon is advocating for more tourism projects in the region and greater government spending on tourism assets. She lists iconic bush walks, mountain bike trails and the West Coast Wilderness Railway as key economic drivers with long-term viability.

She and Steve want to see construction of a hospitality training facility, to create a solid foundation of workers to sustain an expanding industry.

Her own efforts have already paid off. “When we took over Penghana, the tourist season was five months tops, and in winter there was twenty-three per cent occupancy. Now the winters are at forty-three percent, the season is longer. Our income has gone up every year.”

“There’s an element here of ‘when the mine opens again…” notes Berndt. “The way we look at it, we realise it may not ever happen. Tourism has become the new mining, really.”

Elsewhere at Queenstown’s hotel bars and its cafes, talk quickly gets to when the mine might reopen. You’ll hear there’s plenty of ore in the mountains, enough for 50 years by some estimates.

There’s also a recognition that mining has changed.

This time around, there’ll be more waste to dispose of. A century ago, Mt. Lyell yielded ores with 4% copper and more. What will come out of the mountain now is about a quarter of that, sufficient to be profitable, as long as the mine maintains the cost-efficiency of high volumes.

Concentrated ore will be trucked in B-Doubles to Melba Flats at Zeehan, then railed to Burnie. Vessels contracted to Vedanta, the parent company of the mine owner, will ship it to one of its refineries and then a copper rod plant, both in India.

The biggest single player in the economy of this new Queenstown, ironically, is Mt. Lyell’s Abt railway, a tiny 28-tonne steam loco now transporting visitors the 34 kilometres between Queenstown and Strahan.

It’s a reworking of the mine’s original copper concentrate haulage route, today called the West Coast Wilderness Railway, and carrying close to 36,000 passengers a year. That’s a truck load of people taking up hotel rooms, meals and coffee in Queenstown and Strahan for day and half-day trips.

Fresh off a major tourism award in 2019, WCWR general manager Anthony Brown is aiming to make that number 50,000 a year. His optimism spills over into his role as chair of the local tourism association.

“There’s a real excitement about this place, starting with this mountain biking track, and the fact it can be built in about 18 months,” he notes. “All of this is bringing people back into town.”

And the mine? “It’s not if, but when,” says a confident Mr. Brown.