The Pole Doctor

Michael Ryan takes the hammer from its hitch on his belt…

THE POLE DOCTOR

Michael Ryan takes the hammer from its hitch on his belt, and circles his subject while simultaneously dispensing a series of well-placed thwacks to the outermost epidermis.

He’s listening intently to what the blows reveal. Most often, they indicate solid, healthy internals, but occasionally – in that split second – the sound comes back hollow.

With that, it’s time to move to a more precise diagnostic tool. He reaches for a German-built device he’s been working with for about a year. The IML-RESI will render a digital readout of what’s going on inside the body in front of him.

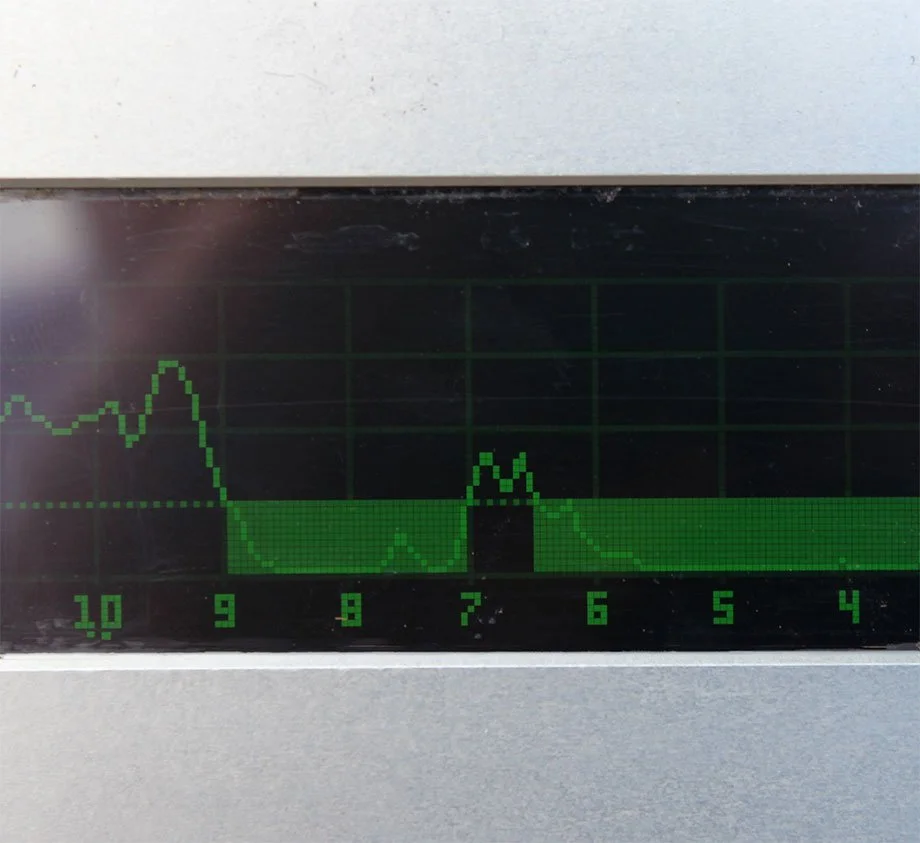

It doesn’t provide a CT scan exactly, but a green squiggly line, much like that of a cardiac monitor. The subject of this scan is a power pole, and it’s talking to Michael Ryan. The news is not good.

On the screen, the green line has dipped into negative territory for some millimetres. What that means, says Ryan, is the IML device’s 3-mm drill bit has hit softer wood. “The pole is rotting from the inside out,” he says bluntly. “It’s well within specs, the thirty mm. of solid wood we need as a minimum, but this is one we’ll keep an eye on.”

Couldn’t that just be a crack in the timber? “No,” he says, pulling up another pole’s digital profile. “See how a crack has much briefer fall and rise on the graph?” Very different readout, very different reason.

Ryan is currently working through what’s called a package of some 400 power poles at Campania, just north of Richmond. He and a colleague Andrew Suffolk started some kilometres apart and are working their way towards each other.

“There’s reasons for working in pairs, mostly safety,” he says. “And sometimes it’s just useful having another pair of eyes looking at what you’re looking at.”

At the base of the pole is a series of black plastic plugs which cover 450 mm tunnels bored at roughly 60 degrees towards the base of the pole.

White sticks of fungicide are inserted into these shafts to keep natural rot at bay and maximise the integrity of the pole at ground-level. As part of his testing regimen, Ryan adds a fresh sticks to each, then replaces the plastic plug.

Michael Ryan came to this job ten years ago after a lengthy stay at Forestry Tasmania. “It’s similar work,” he says, “just that I’ve moved from dealing with live trees to working with dead ones.” He laughs.

One of nine asset inspectors TasNetworks employs in the south of Tasmania (with another 12 in the north) Ryan’s job is to evaluate the health of the company’s poles on a revolving basis. Each gets a thorough checkup every five years.

It’s no small job. Some 290,000 poles are subject to this testing regime.

And like a medical exam, a good deal of information is readily available in, and on, the body of the patient … but only if you know where to look.

A single pole offers up a significant amount of data, much of manifest on its exterior casing. A 40-mm circular medallion sunk into the wood offers what is essentially a birth certificate: it identifies the type of wood, its manufacturing date and the pole length.

A second metallic label identifies the pole by a unique number; TasNetworks knows every one of its poles by that integer, including its location and erection date. A third number, again attached to the outer casing, identifies the pole in sequence, on its own particular street.

Ryan’s attention now turns skyward. He’s looking at the cross arms, sections of hardwood on the outer ends of which are the wires and insulators. This is a process less dependent on clever engineering and a powerful Milwaukee cordless drill, and more on an experienced pair of eyes.

On this particular pole the arm is in need of replacement. A steel support strap has come loose from the wood, and sections of the upper edge are clearly weathered. He moves to record the defect on his Toughpad computer tablet, identifying the pole number and including a semi-close-up photo he’s shot with a tiny camera.

There’s one more job to do. He extracts a spirit level from his tool chest and checks the slant of the pole. This one is straight as a die, but anything beyond 7 degrees is going to get a notation and further scrutiny, possibly straightening or replacement.

The testing job complete, he closes off the job on the tablet. On the screen, a map of this section of Campania appears, each pole identified by a dot. One in a small sea of orange dots turns to green.

The whole process of checking the pole’s internal integrity, and critically, its expected lifespan, has taken perhaps minutes, but this one was straight forward. We move to the next, some 60 metres away.

Ryan’s diagnosis carries a good deal of weight. If necessary, replacement of a dangerously weakened pole could come as soon as 24 hours, a week if things are merely urgent, or 365 days if he considers it will last that long.

“Even an older pole should have at least five more years of life. A total of fifty years is a good span,” he adds.

As poles rot at the base, most obviously just below the soil, a standard technique is to brace it with a steel stake, a hefty V-shaped galvanized steel section that’s rammed deep into the earth beside the wood, then bolted through.

“A stake will add about fifteen years to a pole’s life,” he notes. “But the steel, too, needs to be checked for corrosion, especially here at the soil surface.” He uses the claw of the hammer to expose the base of the steel.

Similarly, square-section steel poles, used as intermediates between poles and homes, get a close examination. Any breakdown in the galvanized coating is reported.

A wood pole, despite its weakness through the natural process of decay, garners support from the chain of poles of which it’s a part, as well as brace poles (usually on the opposite side of the street) and the cabling that runs on the diagonal to nearby homes. They form a cross hatching of support, like multiple stays on a tent.

The pole’s is a humble but crucial task, keeping aloft massive braided aluminium wires, the top-most high tension strands carrying some 11,000 volts, and lower wires 415, after being stepped down by transformers. The cables delivering power to homes are reduced again to the familiar 240 volts.

We move to a new pole, one less than 10 years old. It’s already getting the once-over, beginning with a check with a test pen for any signs of leakage from the wires above. Even a wooden power pole can conduct electricity.

When Ryan is satisfied, he nails a new marker – a piece of rectangular steel plate – at head height, then from his pocket pulls a square-headed punch. With a succession of small blows, the numbers 11 and 19 appear on the plate.

Like a medical record, he’s documenting the date of the first in a regular history of checkups.

Then it’s back to the computer tablet, and at the touch of his fingertips, another orange dot turns green. Just 289,998 poles to go.

THE WORLD ACCORDING TO KERR

THE MAN HIMSELF

THE NOT SO REAL WORLD

THE KERR-LECTION