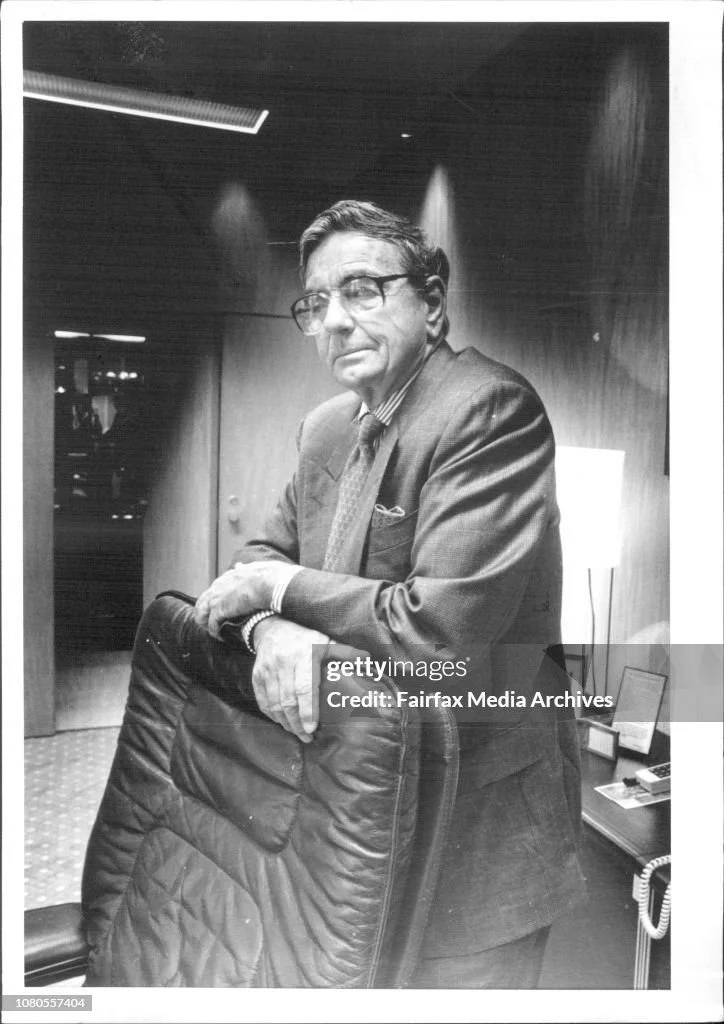

WAK: Robert Johnson

The Chairman of the Australian Trade Commission, Robert Johnson, died on May 7th, 1995. I know this, because I was there.

WAK: ROBERT JOHNSON

Johnston came to Detroit in May of 1995 to officiate at the opening of a new Austrade office. He was the ideal choice: a former chairman of Toyota Australia, and well known across the automotive sector worldwide, he was now chair of the Australian Trade Commission.

And Austrade was in expansionist mode. The recently appointed Executive General Manager for the Americas, Alex Stuart, had been brought out of the private sector (McKinsey & Company) to bring commercial smarts to a government agency.

Among the structural changes driven by Stuart was a reorganisation of the agency’s business expertise across the US and South America.

Promoting Australia’s maritime export interests went to a Houston office, food and consumer goods to New York, film/TV and market research to Los Angeles (also Stuart’s HQ) and the burgeoning automotive sector, of course, to Detroit.

(The final element of that strategy, an office dedicated to the IT and computer sector, saw the opening of an Austrade office in Silicon Valley a few months later.)

The Detroit office, in an office tower overlooking one of the city’s many Ford plants, had a high-tech image of planet Earth installed over its entranceway. It was to be run by a former senior executive from Chrysler that Stuart had recruited.

(I was there at Stuart’s request. He’d hired me a year earlier to handle Austrade’s communications, wherever needed across the Americas, and we worked closely together. It was a contractual arrangement that continued into the early 2000s.

On this occasion, I focussed on getting the US automotive trade press interested in the story of Austrade, Australia’s principal driver of exports, opening for business in Detroit, so invited them and briefed them on the event.)

Johnston’s arrival in Detroit, although planned, was a surprise in one core aspect. He was in a wheelchair, not something Austrade’s management in Sydney had told us to prepare for.

Johnston kind-of explained this quietly to me a little later: he’d had his hip joints replaced two days earlier, not long before getting on the plane to the US. It was likely, I surmised, that nobody at Austrade even knew he was getting on an international flight with his joints still fresh out of the box.

It mattered not. Robert Johnston handled the opening, the ribbon cutting, the speech making, the glad-handing and the interactions with aplomb, and more, a large smile on his face. He knew what he was doing. And if was feeling pain or any discomfort, he did not show it.

Afterwards, for reasons probably related to the fact I was also booked on a flight (mine back to Los Angeles) that I got the job of taking Robert Johnston to his plane at Detroit Airport and the next leg of his US trip.

Mr Johnston was moving out of Austrade mode and into that of a private citizen, now going to join old buddies – automotive industry associates – in Houston.

They were going to play golf. And this was made plain by the fact Mr Johnston had his golf bag across the handles of his wheelchair as we traversed the innards of Detroit Airport.

For those unfamiliar with this particular facility, it is several miles of concourses, walkways, tunnels, passages and sudden turns to the right.

We – Robert Johnston in the chair and me pushing – made good time. There’s a lot to be said for the command and control of a man in a wheelchair with a full set of golfclubs across its steel handles.

We were close to the aircraft gate when I ventured a question of a man now freed from his official responsibilities and looking forward to a few rounds in Houston.

Eyeing the golf clubs, I asked: “Mr Johnston? Tell me: what’s your handicap?”

Johnston didn’t hesitate. He half-turned towards me and answered, clearly and with wicked glint in his eye, “My fucking legs don’t work!”

I don’t remember actually getting him onto the aircraft, but I’m confident he made it on time. I may well have still been laughing at the joke he’d made at his own expense. He had the timing of a pro.

The story should end there, but it doesn’t. I caught my own flight home to Los Angeles, and then drove to Santa Paula where I lived in a cottage with my wife and three children. The phone calls started immediately.

“Did you take Mr Johnston to the airport?” asked the first caller. “did he catch his plane?”

“We can’t seem to find Mr Johnston,” said the next voice, from higher up in Austrade management. “That’s why we’re checking that he made it to the plane okay.”

The phone line between Austrade in Sydney and a little house about 75 miles northwest of Los Angeles was suddenly running hot. I assured them we, Mr Johnston and I, had reached the gate at Detroit Airport in plenty of time.

The phone calls from Sydney continued. Finally, one of the voices said: “We’ve found him at his hotel in Houston.”

“Thank heavens,” I said.

“He’s dead,” the voice added. Holy hell.

The phone calls moved further upstairs. “Can you tell me how was

Mr Johnston’s mood? Was everything …?”

I was now getting phone calls from a Parliamentary office. “Look, Mr Kerr. We’re about to go into the House, and we need to make a statement, say something about Mr Johnston and his work for Austrade.

“So how was he when you last saw him? What was his mood? How did he look to you?”

And then: “What did you talk about? His last words?”

I took a deep breath. Wow, I thought. Robert Johnston’s last words…

I decided in that moment that discretion was the better part of valour, and if that meant misleading the Australian Parliament, so be it. This was not the moment for disclosing Johnston’s wicked sense of humour.

“Mr Johnston was in a good mood,” I said, sticking to a kind of impromptu script. “He was in his wheelchair, yes, but didn’t appear to be in any pain. And he was looking forward to playing golf in Houston, seeing old friends.”

The 180-word speech to the Parliament about Johnston – made by the prime minister, Paul Keating, on May 8 of 1995 – hit all the right notes. Johnston, he pointed out, worked tirelessly and despite illness to push Australia towards exports. He was a true captain of industry, to use an old-fashioned term.

I learned later from Austrade management that it was believed likely that Robert Johnston had died as a result of some kind of post-surgical complication. Robert Johnston’s legs did not work, as he said, and in fact were working against him.

As Dr Chris Cunneen’s entry about Johnston in the Australian Dictionary of Biography notes that he’d faced down illness, including several cancers, such as brain cancer in early 1995, just weeks prior.

The biographer also notes that Johnston had lost an eye as a result, and wore an eye patch for some time. He was, added Dr Cunneen, “soon back at work.”

At the time of his death in the United States, Robert Johnston was doing what he’d always done in the face of his health issues. He toughed it out and got the job done.

So why tell this story now, 29 years after the very distant death of Robert Johnston, AO?

Dr Cunneen, his biographer from Macquarie University, recently noted that he had few sources from which to draw information about Robert Johnston, who had long since divorced and was childless.

For my own part, this is an unknown story about one of the captains of Australian industry. Ours was a brief encounter, but telling.

More, as a participant, I believe any family members – Dr Cunneen notes a nephew and a niece – ought to be given the option of learning a little more about Johnston.

Finally, it’s a damn fine story about a damn fine man, and should be told.

THE WORLD ACCORDING TO KERR

THE MAN HIMSELF

THE NOT SO REAL WORLD

THE KERR-LECTION